Meet three social scientist authors of the Fifth National Climate Assessment

One of the strengths of the Fifth National Climate Assessment is its expanded inclusion of social science across every part of the new report. We caught up with three NOAA authors of the climate assessment to hear how social science when combined with physical science can help our nation find and put to work solutions to the climate crisis with equity and effectiveness.

Ariela Zycherman

Agency chapter lead for the Social Systems and Justice chapter and chapter author for the Overview chapter, from NOAA’s Climate Program Office, Climate and Societal Interactions Division.

Caption: Ariela Zycherman prepares for a kayak trip in the coastal waters off Stonington, Maine. Photo courtesy of Ariela Zycherman.

Why did you take on this role of a lead author?

Serving as an agency chapter lead for the Social Systems and Justice chapter and an author on the Overview chapter has been one of the most exciting moments of my career as a federal social scientist. I am trained as an environmental and applied anthropologist, and my interests are in understanding the complex ways communities and households engage with their environments and find meaning in them. These patterns are shaped both by internal cultural systems and by larger systems of economics, politics, society and environment. Often, there is a dominance of physical data in climate assessments. This information is vital to understanding climatic hazards, but it is most impactful when combined with social data, which offers important contextual information on why and how these hazards create serious risks for communities, as well as how this information might be used with economic, political, or social knowledge to make practical, implementable and effective decisions.

Focusing on just physical data can also mask inequalities in why impacts are more severe in one area than another, as often it is not just the risk of a storm, for example, but the investments or lack of investments in resilient infrastructures that can exacerbate the storm’s impacts. In the Fifth National Climate Assessment, there is a clear understanding that humans are at the center of climate change, this includes as drivers of it, recipients of its impacts, and creators of resilience building actions. For me, the incorporation of social sciences, like anthropology, across the NCA is a long awaited and celebrated step in thinking comprehensively about climate change and it opens up doors to have meaningful conversations about peoples’ experiences of climate change and how real, effective, equitable and lasting solutions can be developed.

What are the Main Messages of your Chapter?

- Social systems are changing the climate and distributing its impacts inequitably. Social systems refers to the institutions, policies, programs, practices, values, behaviors and governance models that shape our assumptions and activities around climate change, these systems not only drive processes that create climate change, like the production of greenhouse gases and where, but also where risks to climate hazards are greatest because of processes of investment or disinvestment in communities over time.

- Social systems structure how people know and communicate about climate change. People’s experiences with climate change are guided by their educations, cultures, traditions, economies, values and uses of and changes to their environments. This diversity of approaches shapes how people interpret and/or drive the changes around them, as well as respond to climate change. To address climate change, processes that engage with multiple ways of knowing, like co-production, help create relevant and appropriate solutions.

- Climate justice is possible if processes like migration and energy transitions are equitable. Climate justice recognizes that the inequitable distribution of resources and other social and political capital impacts the capacity for adaptation during the upheaval created by climate change. Adaptive and mitigative actions, like migration or using renewable energy technologies, have the potential to create co-benefits that not only address climate change, but also remediate past injustices.

Main Challenges?

Rather than focus on challenges, I would like to focus on my hope for a positive climate future. The chapter argues that a just transition is possible. A just transition refers to mitigating and adapting to climate change in a managed process that ensures equitable access to jobs, environmental goods and quality of life. The chapter highlights that we already have the tools to think through how justice can be applied to not only understanding how climate injustices have come about, but also to the creation of implementable adaptation and mitigation actions. By focusing on the complexities of governance models, including legal, political and decisional spaces, decision makers and communities can focus on the structural issues that create inequities and then identify approaches to incorporate multiple perspectives and ensure adequate resources are available to implement them.

Monica Grasso

Agency chapter lead for the Economics chapter and NOAA’s Chief Economist

Caption: Monica Grasso enjoys a day of taking photos of waterfowl and marsh birds in Isle of Wight Park in Worcester County, Maryland. Photo courtesy of Monica Grasso

Why did you take on this role of lead author?

The opportunity to participate in the development of the first Economics chapter in the National Climate Assessment was a one of a kind opportunity to work with experts and show the state of our knowledge of the economic impacts from our changing environment. I have a passion for nature and the outdoors and this was the reason I decided to become an economist. Economics is a common language between individuals and businesses and I wanted to pursue the challenge of demonstrating how natural resources bring value to society.

Main messages of your chapter?

Extreme weather events affect the U.S. economy in many different ways, impacting transportation, agricultural production, tourism and many other economic activities. The increase in frequency and intensity of these events are expected to impose new costs to the U.S. economy and potentially slow our economic growth. We already see some markets and budgets responding to current and anticipated climate changes, and we expect stronger responses as climate change progresses. For example, as the risk of climate extremes grows, new costs and challenges will emerge in insurance systems and public budgets that were not originally designed to respond to climate change. Another important issue is that we expect that these impacts from climate extremes will be unequal across different communities, affecting certain regions, industries and socioeconomic groups more than others.The inequality comes from the fact that certain communities and individuals are more sensitive to climate, have more exposure to these events, and/or lack the resources to adapt and recover from the damages caused by these extreme events.

Main challenges?

One of the major challenges we identified during this process is how to deal with the uncertainty related to the unknown trajectory of future greenhouse gas emissions and associated risks. The uncertainty caused by climate change is itself an economic burden since most individuals and businesses are generally risk averse. As the risk of climate extremes grows, we expect new costs and challenges to emerge in insurance systems, public budgets and other economic systems that were not originally designed to respond to climate change. For example: anticipation of future flood risks has begun to reduce the prices of vulnerable properties. But there are still barriers that prevent market prices from adjusting to reflect climate risks due to inaccurate information or incomplete understanding of the relevant climate risks. In addition, there are also broad research gaps remaining about unequal climate change impacts across demographics, people with differing health status, and socio-economic background.

Promising adaptation example

America’s energy transition will create new economic opportunities, as increased demand for clean energy and low-carbon technologies leads to long-term expansion in most states’ energy and decarbonization workforce. New job opportunities are anticipated to support new and emerging technologies, as well as increased demand for energy efficiency retrofits, clean energy, and resilience measures. For example, grid expansion and energy efficiency projects are already creating new jobs in a number of states.

Caitlin Simpson

Agency chapter lead for the Adaptation chapter from NOAA’s Climate Program Office Climate and Societal Interactions Division

Caption: Caitlin Simpson enjoys spending time with her dog along the East coast where she likes to let residents know about NOAA’s digital resources on sea level rise and climate change more broadly. Photo courtesy of Caitlin Simpson.

Why did you take on this role of lead author?

With a background in economics and human dimensions research, I have been working on climate adaptation issues for many decades and have been pushing for more transdisciplinary science that combines social, physical and other sciences with close community collaboration and input. I have thoroughly enjoyed contributing to the assessment of this field of practice and helping to highlight the importance of more transformative adaptation that is inclusive of community input. I will continue to bring the Fifth National Climate Assessment findings into the adaptation and resilience dialogues at NOAA.

Main messages of your chapter?

Adaptation efforts are occurring in every region of the U.S. but are insufficient in relation to the pace of climate change. Most of these efforts have been small in scale, incremental in approach, and lack sufficient investment and funding. They need to be transformative, meaning that system-wide changes are needed. For any adaptation activity to be effective, it needs to be both just and equitable. This will require addressing the uneven distribution of climate harms and collaborating with local communities.

Main challenges?

Government, private industry and civil society are planning for climate adaptation in different ways, and each is focusing on a subset of climate vulnerability, such as disaster resilience, risk and liability, and equity and justice, respectively. They need to address compound and complex events instead of individual hazards such as sea level rise, flooding or heat. Climate services need to include community collaboration and ensure broad access for historically disinvested communities. Adaptation activities need to be coordinated and incorporate multiple voices. Transformative adaptation that involves persistent, novel, and significant changes to institutions, behaviors, values, and/or technology will be key. Finally, more and different funding/investment is needed for adaptation as is better financial and evaluation data to determine what adaptation is occurring, how well it is distributed, and the effectiveness of the adaptation solutions.

Promising adaptation example

Approximately 40% of US states have assessed their climate change risks, and a number of cities and localities have begun to take action. For example, the city of New York recently legislated Climate Resiliency Design Guidelines, which include the city’s guidance to builders for the required height of flood protection needed in design standards; the requirements now use climate projections from the New York City Panel on Climate Change. Members of the NOAA-funded Climate Adaptation Partnerships team in the Northeast participate on this panel and have provided their latest findings on the social and physical ramifications of climate change for the city.

Additional resources:

- Climate change impacts are increasing for Americans

- Meet 5 NOAA authors of the National Climate Assessment

- Fifth National Climate Assessment

- NCA5 Atlas

- NCA5 Webinars (upcoming)

- NCA5 Webinars (past webinars recorded)

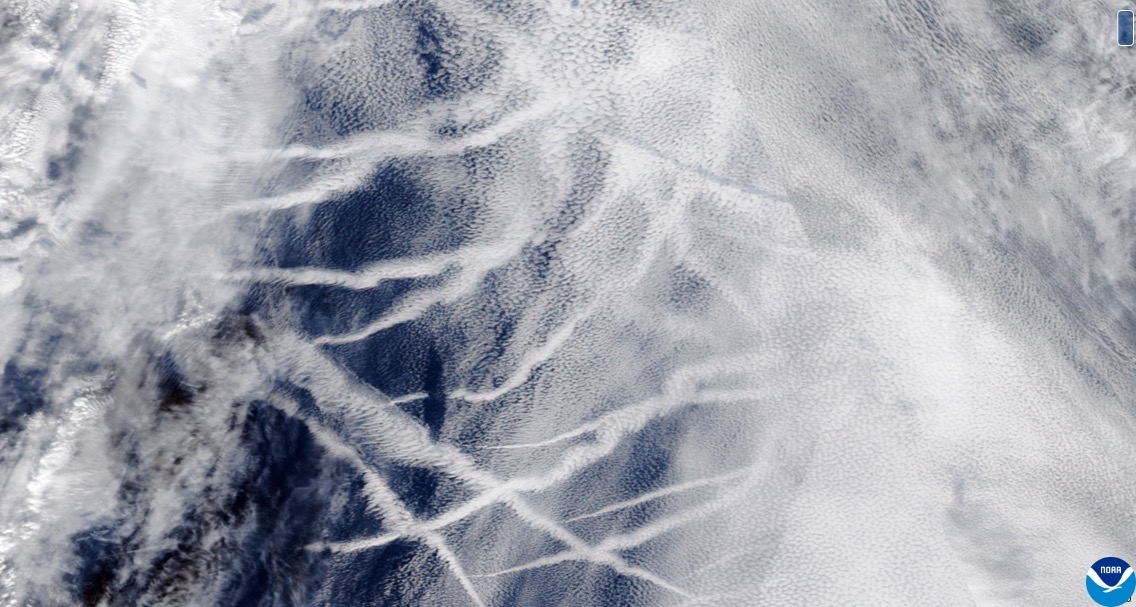

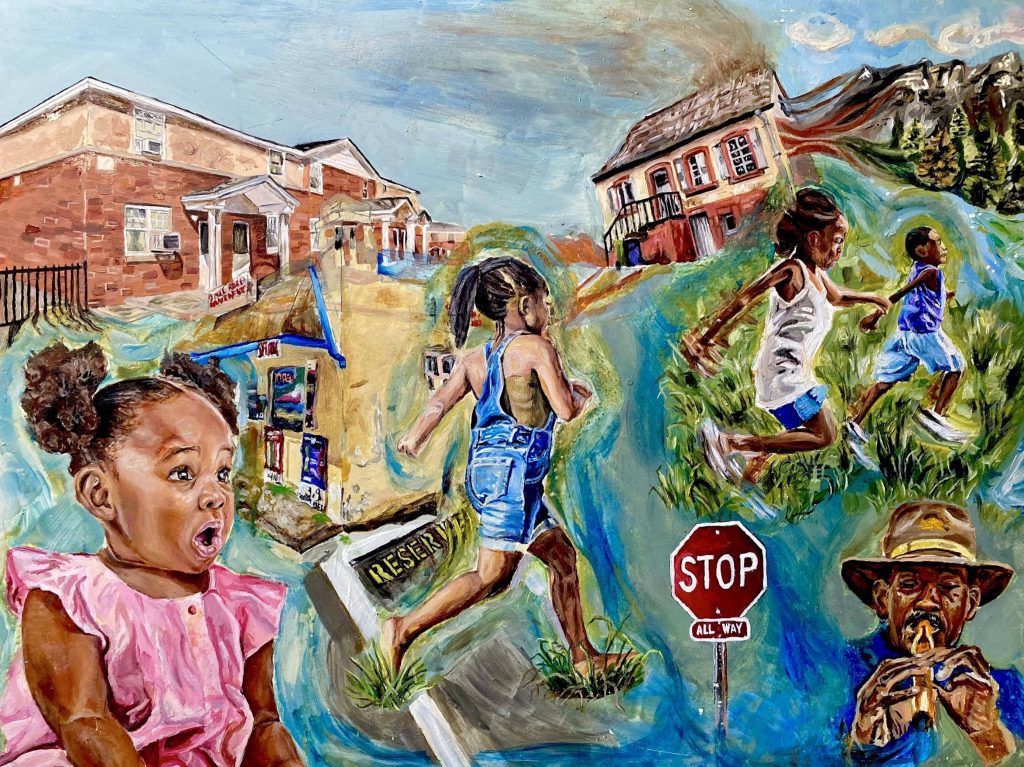

- NCA5 Art X Climate Gallery

For more information, please contact Monica Allen, NOAA Communications, at monica.allen@noaa.gov, 202-379-6693