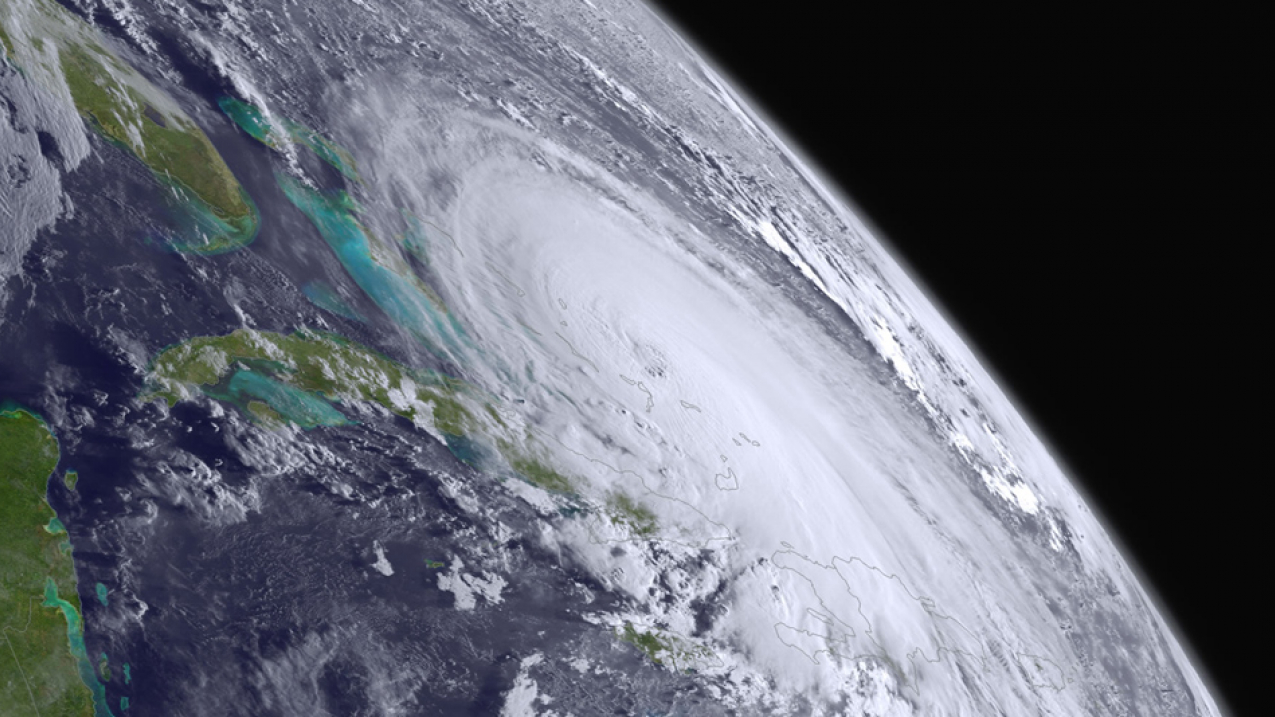

Hurricane Joaquin reaches Category 4 strength near the Central Bahamas on October 1, 2015. (Image credit: NOAA)

Hurricane forecasting

Hurricane forecasting

Hurricane impacts

Hurricane hunters

Atlantic hurricanes and climate

What can coastal residents do to prepare?

Forecasting the hazards of a hurricane and their potential impacts starts with data. Hurricane Specialists at NOAA’s National Hurricane Center (NHC) analyze satellite imagery, other observations, and computer models to make forecast decisions and create hazard information for emergency managers, media and the public for hurricanes, tropical storms and tropical depressions.

Key data come from NOAA satellites that orbit the earth, continuously observing tropical cyclones from start to finish. Polar-orbiting satellites fly over the storm about twice a day at a lower altitude, carrying microwave instruments that reveal storm structure. If there’s a chance the cyclone will threaten land, NHC sends U.S. Air Force Reserve and NOAA Hurricane Hunter aircraft to fly through the storm to take detailed observations. NHC’s Hurricane Specialists also analyze a variety of computer models to help forecast tropical cyclones. Each storm is different, and no one model is right every time, so the Specialists’ experience with these different models is crucial to making the best forecast. On average the NHC forecasts are more consistent and have lower errors than the individual global models used in track forecasting.

325

The average number of tropical cyclone advisories issued in the Atlantic (from 1990-2022)

Before a system forms, NHC issues Tropical Weather Outlooks every six hours to discuss areas of disturbed weather and their potential for development for the next seven days. The Tropical Weather Outlook is issued routinely from May 15 until the end of the hurricane season (November 30).

When a tropical cyclone threatens the U.S. coast, NHC confers with meteorologists at NOAA’s National Weather Service Weather Forecast Offices in the path of the storm to coordinate any necessary watches and warnings in those communities.

Every six hours NHC will issue updated text and graphics — all available on hurricanes.gov — that include track and intensity forecasts for the next five days, storm surge watches and warnings, coastal tropical storm and hurricane watches and warnings for wind, along with the chances of and time of arrival of tropical storm force winds at specific locations. A potential storm surge flooding map, peak storm surge graphics, and storm surge watch/warning graphic are included. NHC also posts the same information on social media to ensure a wide distribution.

When watches or warnings are posted for the U.S. coastline, NHC opens a television media pool to give live interviews to national news outlets and local TV stations in the path of the storm. NHC also provides live streams ahead of the television media pool to provide information on potentially threatening storms to the general public.

When it comes to hurricanes, most people think of wind. But water from storm surge at the coast and inland flooding from rainfall claims the most lives.

Hurricane winds are rated from 1 to 5 on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. Based on maximum sustained winds, the scale gives examples of types of potential property damage and impacts.

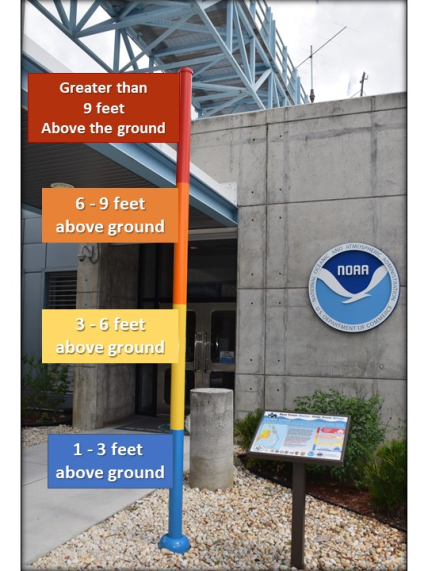

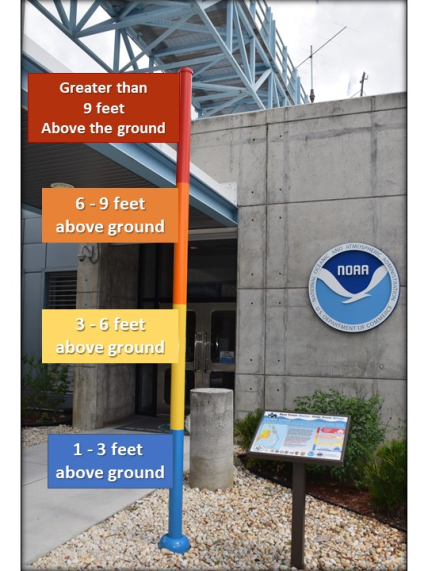

10-15 feet

Flooding levels from the combined effect of storm surge and tides in Fort Myers Beach, Florida during Hurricane Ian in 2022.

Historically, nearly half of the lives lost in hurricanes are related to storm surge, an abnormal rise of water over and above normal levels driven by the hurricane’s winds that can push well inland from the immediate coastline.

To better prepare communities for storm surge, NOAA’s National Hurricane Center has developed a potential storm surge flooding map offsite link, which is released when there is a hurricane or storm surge watch or warning along the U.S. East or Gulf Coasts, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. The map shows a reasonable worst-case scenario where storm surge flooding could occur and gives the height that water could reach above normally dry ground.

Heavy rainfall can extend for hundreds of miles inland, producing extensive inland flooding days after a storm makes landfall as creeks and rivers overflow.

And it isn’t just hurricanes that bring flooding — some of the worst flooding on record has been caused by tropical storms. During the last 10 years, 57% of U.S. fatalities in tropical storms and hurricanes have been due to freshwater flooding from rainfall.

In the last 10 years, 57% of U.S. fatalities in tropical storms and hurricanes have been due to freshwater flooding from rainfall.

The crews of the NOAA and U.S. Air Force Reserve Hurricane Hunter fleet fly around and directly into the storm’s center, measuring weather data to determine the storm’s location, structure and intensity.

When Hurricane Specialists at NOAA’s National Hurricane Center need a closer look at a developing storm or major hurricane, they send special Hurricane Hunter aircraft to fly into it.

152

Total number of missions flown by NOAA and USAF Hurricane Hunters in 2022

NOAA’s Aircraft Operations Center has two WP-3 Orion aircraft that fly out of Lakeland Regional Airport in Florida. These aircraft are used for both operational missions to collect in-storm data, including from the Tail Doppler Radar (TDR), and for research missions to gain a better scientific understanding of hurricanes and test new instruments. The Air Force Reserve has ten WC-130J aircraft at the 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron at Keesler Air Force Base in Biloxi, Mississippi, which fly directly into the core of the storm to gather critical data for forecasting a hurricane’s intensity and landfall.

Flying directly into the storm’s center, these planes drop probes called dropwindsondes at strategic points that continuously transmit critical weather data back to the plane, including pressure, humidity, temperature, wind direction and wind speed. These data give a detailed picture of the storm’s structure and intensity. The planes also collect wind data at flight level and have a special microwave radiometer that measures surface wind and the rate of rain.

All these data are relayed from the plane to a satellite and then to NHC where Hurricane Specialists use it together to assess the cyclone’s location, strength, motion, and size. All of these data, including TDR data from NOAA aircraft are fed into computer models to improve forecasts of hurricane track, intensity and structure, and to help hurricane researchers achieve a better understanding of storm processes.

It’s not always a bumpy ride. NOAA also has a G-IV jet that cruises 45,000 feet above and around a storm. It can cover thousands of square miles around a storm, using dropwindsondes and TDR to collect different types of data from the storm’s core and surrounding environment. The data is sent to NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Prediction in College Park, Maryland, where it’s used in computer models that have been able to improve hurricane track forecasts by about 20 percent in recent years.

Large-scale conditions in the Atlantic and the Caribbean Sea will determine how active or inactive a hurricane season will be.

Scientists say that while the historical record shows an increase in the number of Atlantic hurricanes since the early 1900s, this record does not reflect how much easier it has become to identify hurricanes since we began using satellites. Once this is factored in, scientists say there has been no significant overall increase in Atlantic hurricanes since the late 1800s.

On a shorter time frame, however, the numbers of Atlantic hurricanes have increased, much of it beginning in 1995, as the tropical North Atlantic warmed and atmospheric conditions became conducive to increased hurricane activity, similar to what occurred during the mid-20th century.

One influence is a variation in North Atlantic Ocean temperatures called the Atlantic Multi-decadal Oscillation (AMO), which has cool and warm phases historically lasting 25-40 years each. During its warm phase, North Atlantic sea-surface temperatures are unusually warm compared to the tropical average and the atmospheric conditions over the Atlantic are conducive to hurricane activity. The recent multidecadal variations in Atlantic sea surface temperatures may be partly due to human-caused factors such as dust or other aerosols and partly due to natural climate variability. Scientists are continuing to work to better understand the relative contributions of these factors to the recent multidecadal variability.

Based on a survey of existing studies, with regards to future North Atlantic, Caribbean Sea, and Gulf of Mexico tropical storm and hurricane activity, a 2˚C (4˚F) global warming scenario would be expected to lead to the following:

- Storm inundation levels during hurricane surge events will increase due to sea level rise, anticipated to rise by about 2 to 3 ft (0.4 to 0.8 meters) by 2100.This sea level rise will contribute toward significantly more coastal destruction and increased economic damages.

- Rainfall rates within tropical storms and hurricanes are projected to increase by about 15%.

- Numbers of Atlantic hurricanes reaching Category 4 or 5 intensity are projected to increase about 10% but with large uncertainty and with some studies projecting a decrease.

- Total numbers of Atlantic tropical storms and hurricanes combined are projected to decrease by 15%, but with large uncertainty; a minority of studies project an increase.

- Strongest winds of tropical storms and hurricanes are projected to increase about 3%.

- Other aspects of Atlantic hurricanes – such as named storm formation location, tracks, and size – may also change, but there is little consensus in available projections.

It only takes one storm that affects you to make it a bad hurricane season. If you live along the coast or in areas that could be affected by flooding or hurricane winds, it’s essential to have a personal hurricane plan. This can mean the difference between you being a hurricane victim and a hurricane survivor.

Remember, for a hurricane, most evacuations in the U.S. are due to the impacts of water, not wind. So if you do not live in an evacuation zone and your home is structurally sound, you should shelter-in-place unless otherwise directed to do so. Have the supplies you need to get through the storm and for the potentially lengthy and unpleasant aftermath, with enough non-perishable food, water and medicine to last each person in your family a minimum of one week.

Determine where you would shelter during a storm. In many cases you only need to travel tens of miles to move away from the risk of storm surge. You may be able to find a friend or relative that lives outside the evacuation zone and can ride out the storm with them.

If you need to evacuate, have a “go kit” with personal items you cannot do without during an emergency.

Today you can determine your personal hurricane risk, find out if you live in a hurricane evacuation zone, and review/update insurance policies. You can also make a list of items to replenish hurricane emergency supplies and start thinking about how you will prepare your home for the coming hurricane season. If you live in a hurricane-prone area, you are encouraged to complete these simple preparations before hurricane season begins on June 1. Keep in mind, you may need to adjust any preparedness actions based on the latest health and safety guidelines from the CDC and your local officials.

Waiting until the storm is on your doorstep is too late. Resilience depends on preparation. The websites www.hurricanes.gov/prepare and www.ready.gov will help you make a plan for yourself and your loved ones.

NOAA’s Weather-Ready Nation campaign is about building community resilience in the face of increasing vulnerability to extreme weather and water event, including hurricanes.

The nonprofit Federal Alliance for Safe Homes offsite link

(FLASH®) is a NOAA partner and the country’s leading consumer advocate for strengthening homes and safeguarding families from natural and manmade disasters.

Forecasting the hazards of a hurricane and their potential impacts starts with data. Hurricane Specialists at NOAA’s National Hurricane Center (NHC) analyze satellite imagery, other observations, and computer models to make forecast decisions and create hazard information for emergency managers, media and the public for hurricanes, tropical storms and tropical depressions.

Key data come from NOAA satellites that orbit the earth, continuously observing tropical cyclones from start to finish. Polar-orbiting satellites fly over the storm about twice a day at a lower altitude, carrying microwave instruments that reveal storm structure. If there’s a chance the cyclone will threaten land, NHC sends U.S. Air Force Reserve and NOAA Hurricane Hunter aircraft to fly through the storm to take detailed observations. NHC’s Hurricane Specialists also analyze a variety of computer models to help forecast tropical cyclones. Each storm is different, and no one model is right every time, so the Specialists’ experience with these different models is crucial to making the best forecast. On average the NHC forecasts are more consistent and have lower errors than the individual global models used in track forecasting.

325

The average number of tropical cyclone advisories issued in the Atlantic (from 1990-2022)

Before a system forms, NHC issues Tropical Weather Outlooks every six hours to discuss areas of disturbed weather and their potential for development for the next seven days. The Tropical Weather Outlook is issued routinely from May 15 until the end of the hurricane season (November 30).

When a tropical cyclone threatens the U.S. coast, NHC confers with meteorologists at NOAA’s National Weather Service Weather Forecast Offices in the path of the storm to coordinate any necessary watches and warnings in those communities.

Every six hours NHC will issue updated text and graphics — all available on hurricanes.gov — that include track and intensity forecasts for the next five days, storm surge watches and warnings, coastal tropical storm and hurricane watches and warnings for wind, along with the chances of and time of arrival of tropical storm force winds at specific locations. A potential storm surge flooding map, peak storm surge graphics, and storm surge watch/warning graphic are included. NHC also posts the same information on social media to ensure a wide distribution.

When watches or warnings are posted for the U.S. coastline, NHC opens a television media pool to give live interviews to national news outlets and local TV stations in the path of the storm. NHC also provides live streams ahead of the television media pool to provide information on potentially threatening storms to the general public.

When it comes to hurricanes, most people think of wind. But water from storm surge at the coast and inland flooding from rainfall claims the most lives.

Hurricane winds are rated from 1 to 5 on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. Based on maximum sustained winds, the scale gives examples of types of potential property damage and impacts.

10-15 feet

Flooding levels from the combined effect of storm surge and tides in Fort Myers Beach, Florida during Hurricane Ian in 2022.

Historically, nearly half of the lives lost in hurricanes are related to storm surge, an abnormal rise of water over and above normal levels driven by the hurricane’s winds that can push well inland from the immediate coastline.

To better prepare communities for storm surge, NOAA’s National Hurricane Center has developed a potential storm surge flooding map offsite link, which is released when there is a hurricane or storm surge watch or warning along the U.S. East or Gulf Coasts, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. The map shows a reasonable worst-case scenario where storm surge flooding could occur and gives the height that water could reach above normally dry ground.

Heavy rainfall can extend for hundreds of miles inland, producing extensive inland flooding days after a storm makes landfall as creeks and rivers overflow.

And it isn’t just hurricanes that bring flooding — some of the worst flooding on record has been caused by tropical storms. During the last 10 years, 57% of U.S. fatalities in tropical storms and hurricanes have been due to freshwater flooding from rainfall.

In the last 10 years, 57% of U.S. fatalities in tropical storms and hurricanes have been due to freshwater flooding from rainfall.

The crews of the NOAA and U.S. Air Force Reserve Hurricane Hunter fleet fly around and directly into the storm’s center, measuring weather data to determine the storm’s location, structure and intensity.

When Hurricane Specialists at NOAA’s National Hurricane Center need a closer look at a developing storm or major hurricane, they send special Hurricane Hunter aircraft to fly into it.

152

Total number of missions flown by NOAA and USAF Hurricane Hunters in 2022

NOAA’s Aircraft Operations Center has two WP-3 Orion aircraft that fly out of Lakeland Regional Airport in Florida. These aircraft are used for both operational missions to collect in-storm data, including from the Tail Doppler Radar (TDR), and for research missions to gain a better scientific understanding of hurricanes and test new instruments. The Air Force Reserve has ten WC-130J aircraft at the 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron at Keesler Air Force Base in Biloxi, Mississippi, which fly directly into the core of the storm to gather critical data for forecasting a hurricane’s intensity and landfall.

Flying directly into the storm’s center, these planes drop probes called dropwindsondes at strategic points that continuously transmit critical weather data back to the plane, including pressure, humidity, temperature, wind direction and wind speed. These data give a detailed picture of the storm’s structure and intensity. The planes also collect wind data at flight level and have a special microwave radiometer that measures surface wind and the rate of rain.

All these data are relayed from the plane to a satellite and then to NHC where Hurricane Specialists use it together to assess the cyclone’s location, strength, motion, and size. All of these data, including TDR data from NOAA aircraft are fed into computer models to improve forecasts of hurricane track, intensity and structure, and to help hurricane researchers achieve a better understanding of storm processes.

It’s not always a bumpy ride. NOAA also has a G-IV jet that cruises 45,000 feet above and around a storm. It can cover thousands of square miles around a storm, using dropwindsondes and TDR to collect different types of data from the storm’s core and surrounding environment. The data is sent to NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Prediction in College Park, Maryland, where it’s used in computer models that have been able to improve hurricane track forecasts by about 20 percent in recent years.

Large-scale conditions in the Atlantic and the Caribbean Sea will determine how active or inactive a hurricane season will be.

Scientists say that while the historical record shows an increase in the number of Atlantic hurricanes since the early 1900s, this record does not reflect how much easier it has become to identify hurricanes since we began using satellites. Once this is factored in, scientists say there has been no significant overall increase in Atlantic hurricanes since the late 1800s.

On a shorter time frame, however, the numbers of Atlantic hurricanes have increased, much of it beginning in 1995, as the tropical North Atlantic warmed and atmospheric conditions became conducive to increased hurricane activity, similar to what occurred during the mid-20th century.

One influence is a variation in North Atlantic Ocean temperatures called the Atlantic Multi-decadal Oscillation (AMO), which has cool and warm phases historically lasting 25-40 years each. During its warm phase, North Atlantic sea-surface temperatures are unusually warm compared to the tropical average and the atmospheric conditions over the Atlantic are conducive to hurricane activity. The recent multidecadal variations in Atlantic sea surface temperatures may be partly due to human-caused factors such as dust or other aerosols and partly due to natural climate variability. Scientists are continuing to work to better understand the relative contributions of these factors to the recent multidecadal variability.

Based on a survey of existing studies, with regards to future North Atlantic, Caribbean Sea, and Gulf of Mexico tropical storm and hurricane activity, a 2˚C (4˚F) global warming scenario would be expected to lead to the following:

- Storm inundation levels during hurricane surge events will increase due to sea level rise, anticipated to rise by about 2 to 3 ft (0.4 to 0.8 meters) by 2100.This sea level rise will contribute toward significantly more coastal destruction and increased economic damages.

- Rainfall rates within tropical storms and hurricanes are projected to increase by about 15%.

- Numbers of Atlantic hurricanes reaching Category 4 or 5 intensity are projected to increase about 10% but with large uncertainty and with some studies projecting a decrease.

- Total numbers of Atlantic tropical storms and hurricanes combined are projected to decrease by 15%, but with large uncertainty; a minority of studies project an increase.

- Strongest winds of tropical storms and hurricanes are projected to increase about 3%.

- Other aspects of Atlantic hurricanes – such as named storm formation location, tracks, and size – may also change, but there is little consensus in available projections.

It only takes one storm that affects you to make it a bad hurricane season. If you live along the coast or in areas that could be affected by flooding or hurricane winds, it’s essential to have a personal hurricane plan. This can mean the difference between you being a hurricane victim and a hurricane survivor.

Remember, for a hurricane, most evacuations in the U.S. are due to the impacts of water, not wind. So if you do not live in an evacuation zone and your home is structurally sound, you should shelter-in-place unless otherwise directed to do so. Have the supplies you need to get through the storm and for the potentially lengthy and unpleasant aftermath, with enough non-perishable food, water and medicine to last each person in your family a minimum of one week.

Determine where you would shelter during a storm. In many cases you only need to travel tens of miles to move away from the risk of storm surge. You may be able to find a friend or relative that lives outside the evacuation zone and can ride out the storm with them.

If you need to evacuate, have a “go kit” with personal items you cannot do without during an emergency.

Today you can determine your personal hurricane risk, find out if you live in a hurricane evacuation zone, and review/update insurance policies. You can also make a list of items to replenish hurricane emergency supplies and start thinking about how you will prepare your home for the coming hurricane season. If you live in a hurricane-prone area, you are encouraged to complete these simple preparations before hurricane season begins on June 1. Keep in mind, you may need to adjust any preparedness actions based on the latest health and safety guidelines from the CDC and your local officials.

Waiting until the storm is on your doorstep is too late. Resilience depends on preparation. The websites www.hurricanes.gov/prepare and www.ready.gov will help you make a plan for yourself and your loved ones.

NOAA’s Weather-Ready Nation campaign is about building community resilience in the face of increasing vulnerability to extreme weather and water event, including hurricanes.

The nonprofit Federal Alliance for Safe Homes offsite link

(FLASH®) is a NOAA partner and the country’s leading consumer advocate for strengthening homes and safeguarding families from natural and manmade disasters.