The largest marine oil spill in U.S. history occurred on April 20, 2010 when the BP oil rig, Deepwater Horizon, exploded killing 11 workers and spilling more than 134,000 barrels of oil into the Gulf of Mexico. (Image credit: U.S. Coast Guard)

Oil spills: A major marine ecosystem threat

How and where do oil spills happen?

Controlling oil slicks is critical to protecting sensitive areas

NOAA providing innovation in tools to guide spill response decisions

NOAA: Trustee of marine resources for the American public

Drilling is not the major concern, navigation-borne commerce is

Oil spills that happen in rivers, bays and the ocean most often are caused by accidents involving tankers, barges, pipelines, refineries, drilling rigs and storage facilities, but also occur from recreational boats and in marinas.

Spills can be caused by:

- people making mistakes or being careless

- equipment breaking down

- natural disasters such as hurricanes, storm surge or high winds

- deliberate acts by terrorists, acts of war, vandals or illegal dumping.

Most oils float on the oceans’ saltwater or freshwater from rivers and lakes. Oil usually spreads out rapidly across the water’s surface to form a thin oil slick. As the oil continues spreading, the slick becomes thinner and thinner, finally becoming a very thin sheen, which often looks like a rainbow. (In rare cases, very heavy oil can sometimes sink.)

Depending on the circumstances, oil spills can be very harmful to marine birds, sea turtles and mammals, and also can harm fish and shellfish. Oil destroys the insulating ability of fur-bearing mammals, such as sea otters, and the water-repelling abilities of a bird's feathers, exposing them to the harsh elements. Many birds and animals also swallow oil and are poisoned when they try to clean themselves or when eating oiled prey.

Fish and shellfish can also digest oil, which could cause changes in reproduction, growth rates or even death. Commercially important species such as oysters, shrimp, mahi-mahi, grouper, swordfish and tuna also could suffer population declines or become too contaminated to be safely caught and eaten.

Depending on just where and when a spill happens, from a few up to hundreds or thousands of birds, fish, mammals, reptiles, corals and other animals and plants can be killed or injured.

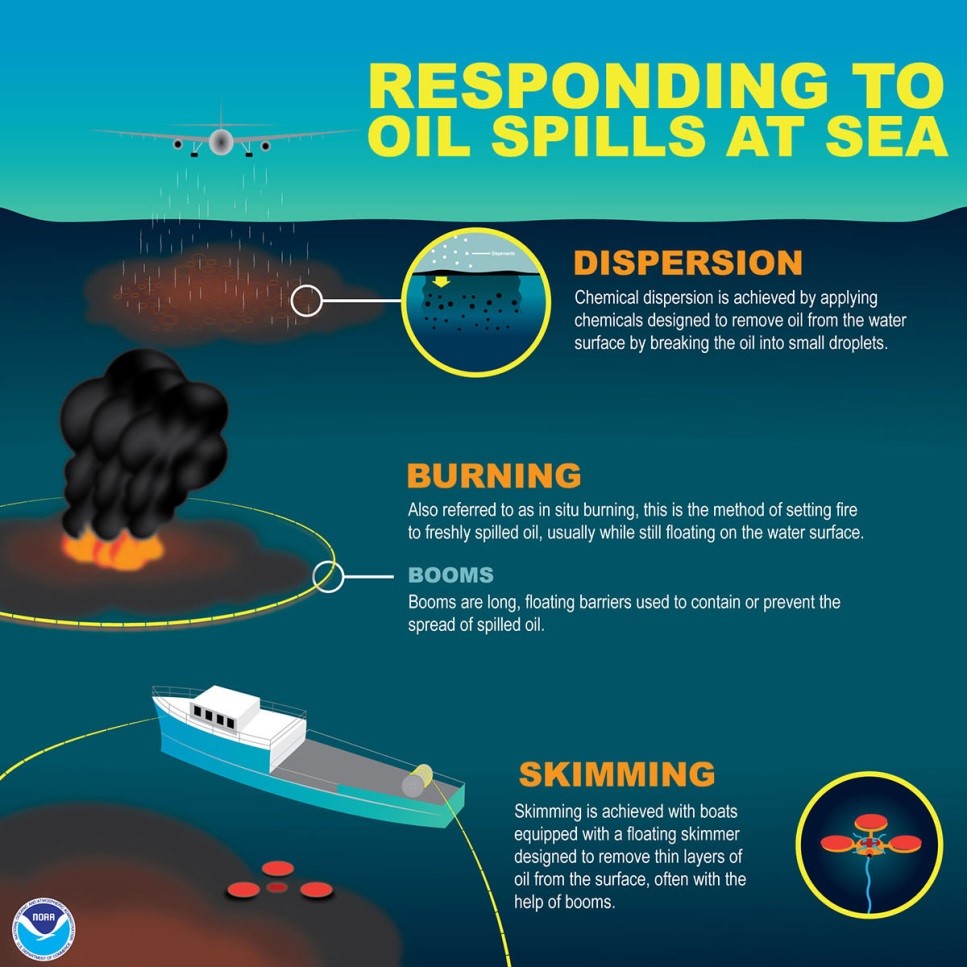

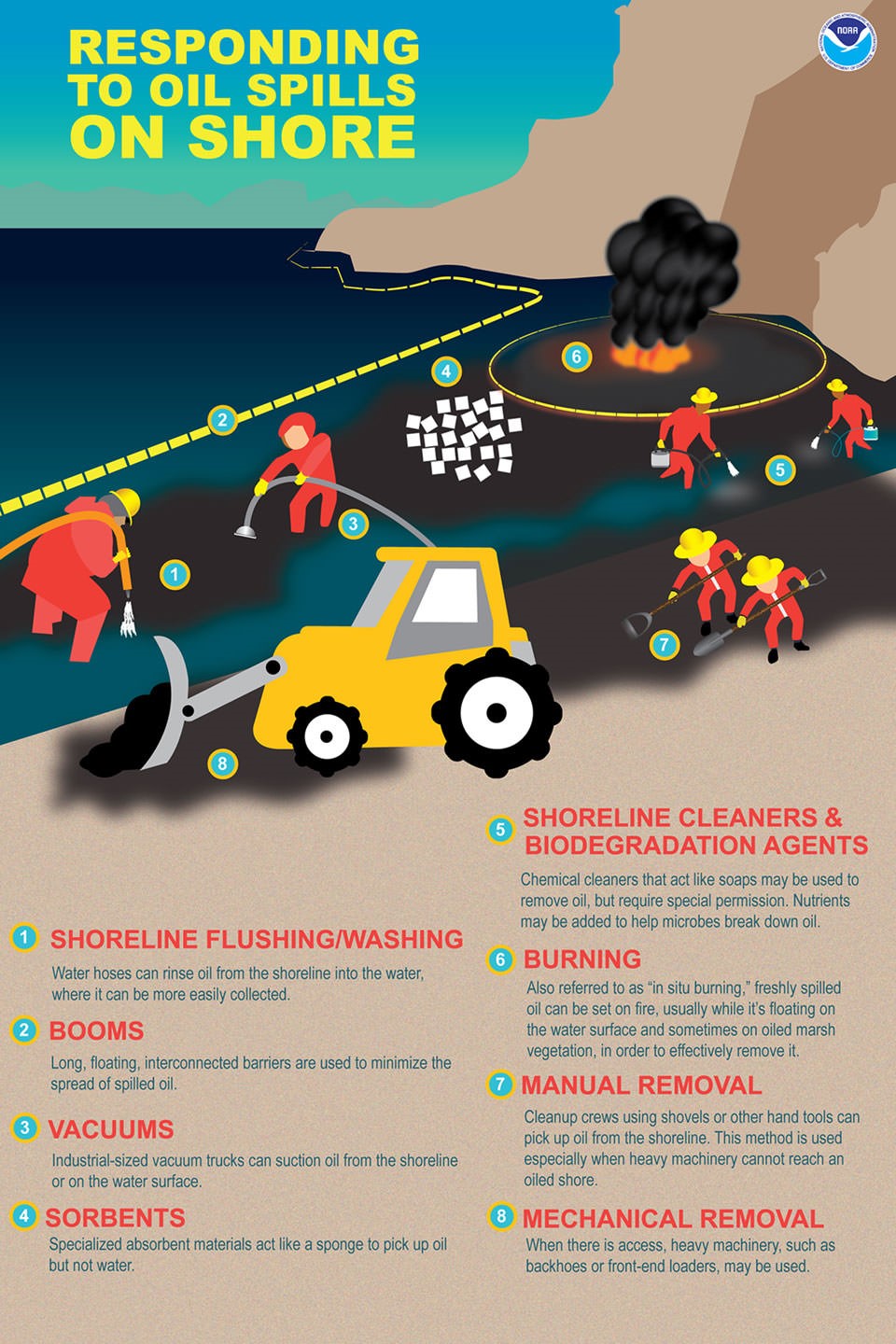

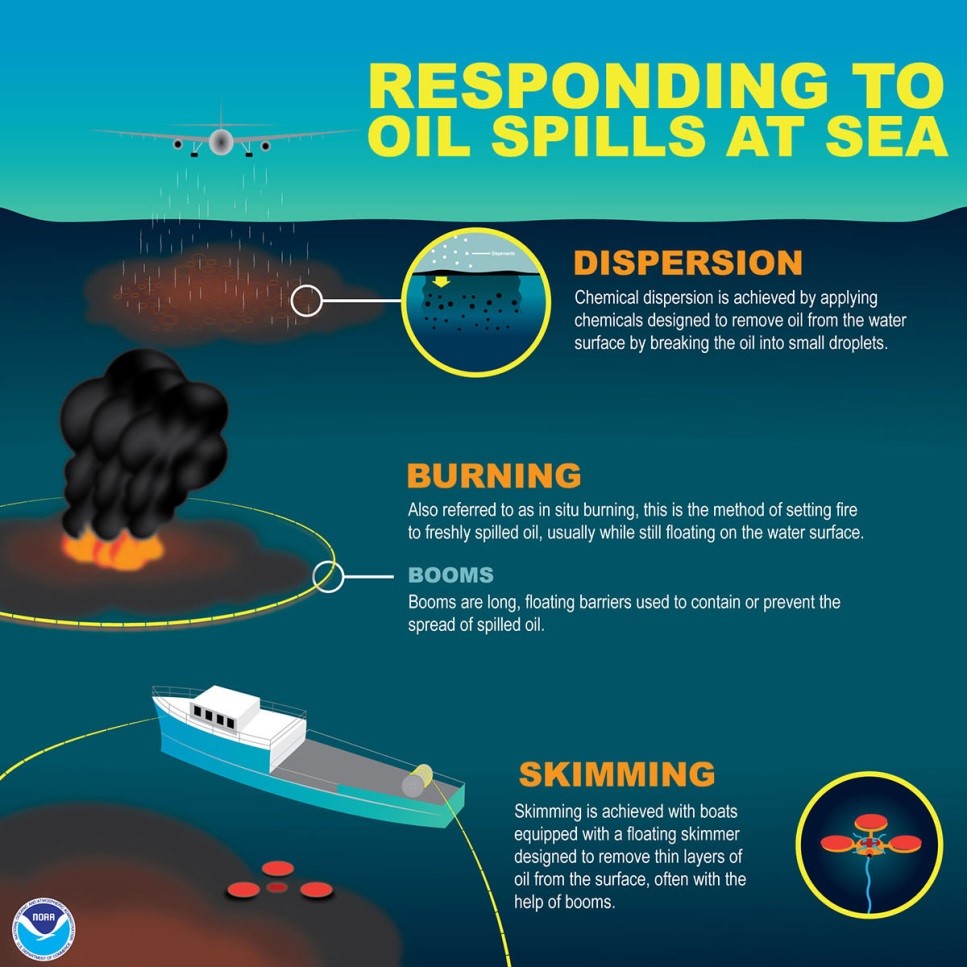

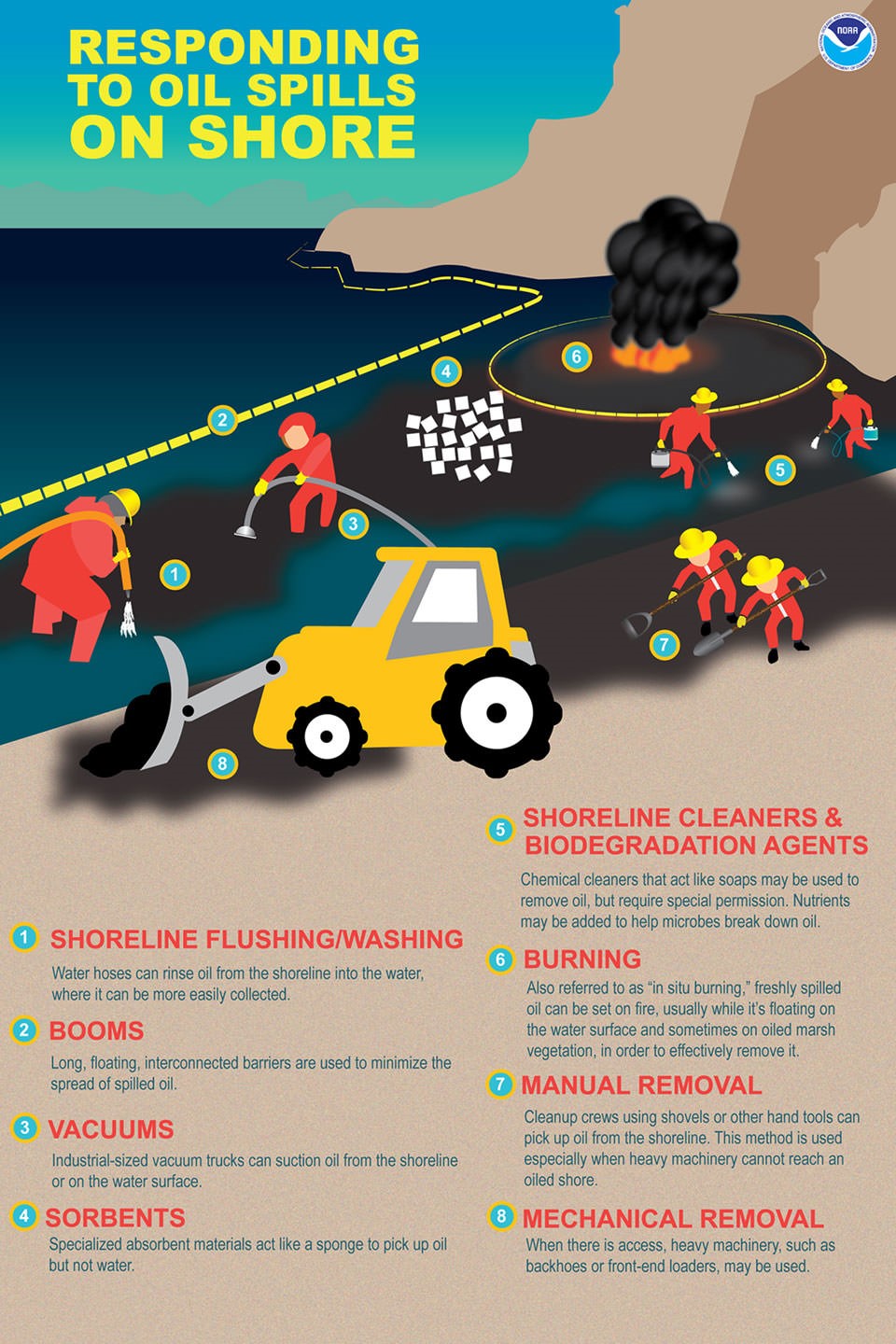

The response to an oil spill has several goals – foremost to stop the flow of the oil or chemical, but also to protect sensitive areas that could be harmed by the spill itself, and to safely remove the oil from the environment as quickly and efficiently as possible.

During a spill response, sensitive locations, like coastal wetlands or animal nesting areas threatened by an oil slick, can be protected with various kinds of equipment and tactics, but the tools used depend on where spill has occurred and type of oil spilled. Some spills evaporate rapidly off the water surface without any active clean-up needed.

1

Quarts of oil in a two-acre oil slick, the size of three football fields.

If local authorities and response experts agree, other possible, but more controversial and rarely used measures include:

-

In situ burning, a method of burning freshly spilled oil, usually while it's floating on the water.

-

Using aircraft or boats to apply dispersants (chemicals that disperse the oil into the water column) so that much less stays at the surface where it could move to coastal wetlands, beaches, and tidal flats endangering critical habitat and nursery areas

-

Responders can use biological agents such as microbes or fertilizers to help break down oil into its chemical constituents.

In most spills a combination of methods are used.

Which methods are selected depends on circumstances of each event: weather; type and amount of oil spilled; how far away from shore oil has spilled; whether or not people live in area; what kinds of bird and animal habitats are in area and other factors.

Since 1969, there have been at least 44 oil spills of more than 10,000 barrels – 420,000 gallons – in U.S. waters.

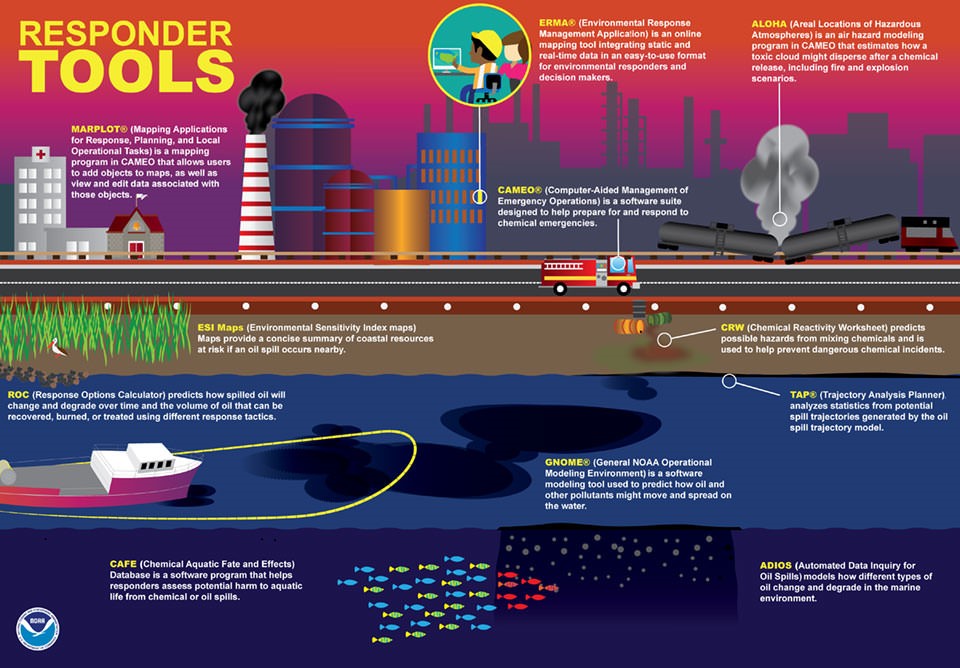

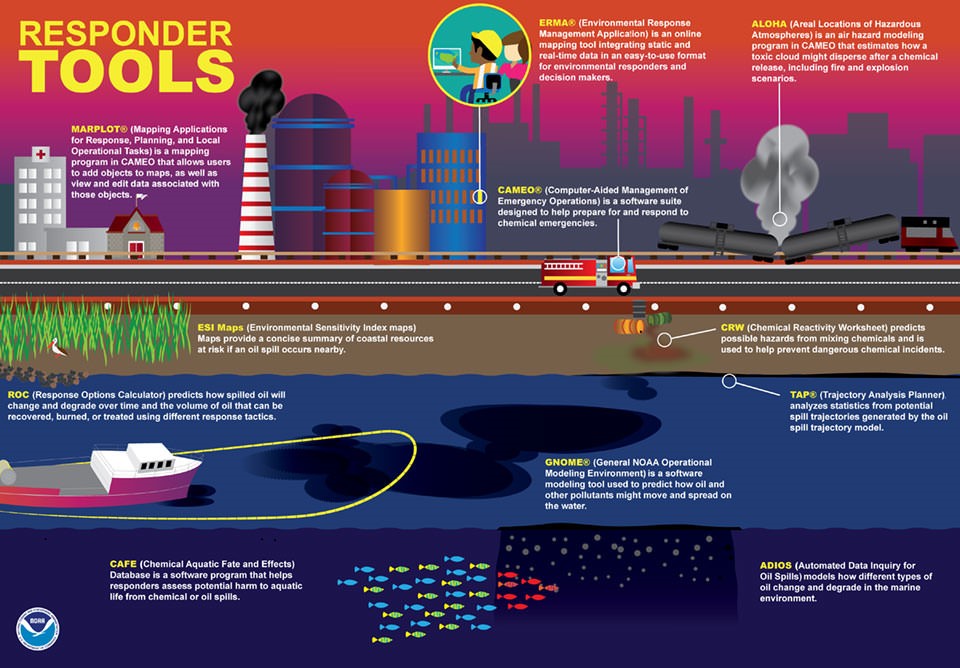

Most recently, in the Deepwater Horizon spill response, NOAA made available, for the first time, an online geospatial mapping system called Environmental Response Management System or ERMA, developed with the University of New Hampshire.

ERMA integrates static and real-time data, such as Environmental Sensitivity Index maps, ship locations, weather and ocean currents, in one easy-to-use format for environmental responders and decision makers. The public can also use ERMA to get a better understanding of what is happening. U.S. Coast Guard Admiral Thad Allen called it “the best thing to have happened out of the spill.” NOAA has since rapidly expanded its development into other regions at risk of a chemical or oil spill.

NOAA, acting in behalf of the American people, is a federal trustee for coastal and marine natural resources, including marine and migratory fish, endangered species, marine mammals and their habitats. Federal laws charge NOAA and certain other federal agencies, states, and Indian tribes with protecting and restoring public natural resources that are affected by oil spills, releases of hazardous substances and ship groundings.

NOAA fulfills its responsibilities by conducting certain key actions after hazardous materials or oil are released into the ocean, marshes, lakes and rivers.

134 million

—Estimated gallons of oil spilled in the 2010 Deepwater Horizon well blowout.

During cleanup of an oil spill or hazardous waste, NOAA scientific experts provide guidance to agencies such as the U.S. Coast Guard and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency that lead the effort. Their goal is to make the most of the cleanup while protecting natural resources.

NOAA is also responsible for the assessment and restoration of river and coastal resources harmed by hazardous material releases. NOAA’s Office of Response and Restoration works with other NOAA offices to form the Damage Assessment, Remediation and Restoration Program.

The Natural Resource Damage Assessment process determines the extent of harm to natural resources and the appropriate type and amount of restoration required to compensate the American public. We work together with the responsible parties to identify both the harm to natural resources and lost recreational uses. Experts determine when and where the injuries took place, and — with public input — the best methods, amounts and locations for restoration.

Since 1988, more than $10.4 billion has been recovered from responsible parties, including up to $8.8 billion in NRDA Deepwater Horizon project funding. The funds are being used to restore damaged estuarine and coastal resources including wetlands, coral reefs, streams and beaches. Environmental restoration benefits fish, birds and marine mammal habitats, and strengthens local and regional economies.

The formerly mythical Northwest Passage has become a reality due to climate change. Conditions in the Arctic are changing rapidly. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change offsite link estimates that within the next 80 years, the Arctic Ocean could be ice-free in the summer and potentially year round – leading to rapidly increasing opportunities for maritime transportation, tourism and oil and gas exploration.

Ice-free conditions still present hazards to navigation: moving ice floes, unsettled weather and wave patterns. Emergency responders are few and far between. This means that when oil does spill, consequences can be much more severe, and search and rescue missions face even greater difficulties. Marine navigational charts for much of the region were made using lead-line measurements--dropping a lead weight on a string and figuring how much rope is let out until it hits the bottom. These measurements can date back to as early as the 18th century through World War II. Less than 1 percent of the U.S. Arctic has been surveyed with modern technology.

At least 44

—Oil spills of more than 10,000 barrels – 420,000 gallons – in U.S. waters since 1969.

The Arctic is one of the most remote areas on earth. How would hundreds of responders would get there, along with all their heavy equipment such as booms, skimmers, and vessels? Once deployed, response equipment has the potential to ice-over, encounter high winds, or be grounded from dense fog. Communicating with responders and decision makers on other ships, on shore at a command post, or even farther away in the lower 48 states will be an enormous challenge.

Also, we don’t know precisely how the many oils and chemicals that could be spilled into the frigid Arctic waters will react to the conditions there--the cold, the water’s salinity, ocean currents altered by weather conditions not seen elsewhere--and how traditional response tools of booms, skimmers, dispersants, and microbes will function in this extreme climate.

Technology maybe the key to a successful response should a spill ever occur. NOAA and the U.S. Coast Guard have partnered in a series of annual simulated spill response exercises to try a variety of new technologies to offset the lack of in-place infrastructure. Among the tools being tested are unmanned aerial aircraft, autonomous underwater vehicles, balloons with cameras, as well as drifter buoys tracked by space satellites. Additionally NOAA, the Coast Guard and regional partners have been working with industry and academia to fill the Arctic ERMA mapping system with advanced scientific based information concerning natural resources, communities and existing infrastructure that could be affected, as well as developing proposed response plan scenarios.

Oil spills that happen in rivers, bays and the ocean most often are caused by accidents involving tankers, barges, pipelines, refineries, drilling rigs and storage facilities, but also occur from recreational boats and in marinas.

Spills can be caused by:

- people making mistakes or being careless

- equipment breaking down

- natural disasters such as hurricanes, storm surge or high winds

- deliberate acts by terrorists, acts of war, vandals or illegal dumping.

Most oils float on the oceans’ saltwater or freshwater from rivers and lakes. Oil usually spreads out rapidly across the water’s surface to form a thin oil slick. As the oil continues spreading, the slick becomes thinner and thinner, finally becoming a very thin sheen, which often looks like a rainbow. (In rare cases, very heavy oil can sometimes sink.)

Depending on the circumstances, oil spills can be very harmful to marine birds, sea turtles and mammals, and also can harm fish and shellfish. Oil destroys the insulating ability of fur-bearing mammals, such as sea otters, and the water-repelling abilities of a bird's feathers, exposing them to the harsh elements. Many birds and animals also swallow oil and are poisoned when they try to clean themselves or when eating oiled prey.

Fish and shellfish can also digest oil, which could cause changes in reproduction, growth rates or even death. Commercially important species such as oysters, shrimp, mahi-mahi, grouper, swordfish and tuna also could suffer population declines or become too contaminated to be safely caught and eaten.

Depending on just where and when a spill happens, from a few up to hundreds or thousands of birds, fish, mammals, reptiles, corals and other animals and plants can be killed or injured.

The response to an oil spill has several goals – foremost to stop the flow of the oil or chemical, but also to protect sensitive areas that could be harmed by the spill itself, and to safely remove the oil from the environment as quickly and efficiently as possible.

During a spill response, sensitive locations, like coastal wetlands or animal nesting areas threatened by an oil slick, can be protected with various kinds of equipment and tactics, but the tools used depend on where spill has occurred and type of oil spilled. Some spills evaporate rapidly off the water surface without any active clean-up needed.

1

Quarts of oil in a two-acre oil slick, the size of three football fields.

If local authorities and response experts agree, other possible, but more controversial and rarely used measures include:

-

In situ burning, a method of burning freshly spilled oil, usually while it's floating on the water.

-

Using aircraft or boats to apply dispersants (chemicals that disperse the oil into the water column) so that much less stays at the surface where it could move to coastal wetlands, beaches, and tidal flats endangering critical habitat and nursery areas

-

Responders can use biological agents such as microbes or fertilizers to help break down oil into its chemical constituents.

In most spills a combination of methods are used.

Which methods are selected depends on circumstances of each event: weather; type and amount of oil spilled; how far away from shore oil has spilled; whether or not people live in area; what kinds of bird and animal habitats are in area and other factors.

Since 1969, there have been at least 44 oil spills of more than 10,000 barrels – 420,000 gallons – in U.S. waters.

Most recently, in the Deepwater Horizon spill response, NOAA made available, for the first time, an online geospatial mapping system called Environmental Response Management System or ERMA, developed with the University of New Hampshire.

ERMA integrates static and real-time data, such as Environmental Sensitivity Index maps, ship locations, weather and ocean currents, in one easy-to-use format for environmental responders and decision makers. The public can also use ERMA to get a better understanding of what is happening. U.S. Coast Guard Admiral Thad Allen called it “the best thing to have happened out of the spill.” NOAA has since rapidly expanded its development into other regions at risk of a chemical or oil spill.

NOAA, acting in behalf of the American people, is a federal trustee for coastal and marine natural resources, including marine and migratory fish, endangered species, marine mammals and their habitats. Federal laws charge NOAA and certain other federal agencies, states, and Indian tribes with protecting and restoring public natural resources that are affected by oil spills, releases of hazardous substances and ship groundings.

NOAA fulfills its responsibilities by conducting certain key actions after hazardous materials or oil are released into the ocean, marshes, lakes and rivers.

134 million

—Estimated gallons of oil spilled in the 2010 Deepwater Horizon well blowout.

During cleanup of an oil spill or hazardous waste, NOAA scientific experts provide guidance to agencies such as the U.S. Coast Guard and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency that lead the effort. Their goal is to make the most of the cleanup while protecting natural resources.

NOAA is also responsible for the assessment and restoration of river and coastal resources harmed by hazardous material releases. NOAA’s Office of Response and Restoration works with other NOAA offices to form the Damage Assessment, Remediation and Restoration Program.

The Natural Resource Damage Assessment process determines the extent of harm to natural resources and the appropriate type and amount of restoration required to compensate the American public. We work together with the responsible parties to identify both the harm to natural resources and lost recreational uses. Experts determine when and where the injuries took place, and — with public input — the best methods, amounts and locations for restoration.

Since 1988, more than $10.4 billion has been recovered from responsible parties, including up to $8.8 billion in NRDA Deepwater Horizon project funding. The funds are being used to restore damaged estuarine and coastal resources including wetlands, coral reefs, streams and beaches. Environmental restoration benefits fish, birds and marine mammal habitats, and strengthens local and regional economies.

The formerly mythical Northwest Passage has become a reality due to climate change. Conditions in the Arctic are changing rapidly. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change offsite link estimates that within the next 80 years, the Arctic Ocean could be ice-free in the summer and potentially year round – leading to rapidly increasing opportunities for maritime transportation, tourism and oil and gas exploration.

Ice-free conditions still present hazards to navigation: moving ice floes, unsettled weather and wave patterns. Emergency responders are few and far between. This means that when oil does spill, consequences can be much more severe, and search and rescue missions face even greater difficulties. Marine navigational charts for much of the region were made using lead-line measurements--dropping a lead weight on a string and figuring how much rope is let out until it hits the bottom. These measurements can date back to as early as the 18th century through World War II. Less than 1 percent of the U.S. Arctic has been surveyed with modern technology.

At least 44

—Oil spills of more than 10,000 barrels – 420,000 gallons – in U.S. waters since 1969.

The Arctic is one of the most remote areas on earth. How would hundreds of responders would get there, along with all their heavy equipment such as booms, skimmers, and vessels? Once deployed, response equipment has the potential to ice-over, encounter high winds, or be grounded from dense fog. Communicating with responders and decision makers on other ships, on shore at a command post, or even farther away in the lower 48 states will be an enormous challenge.

Also, we don’t know precisely how the many oils and chemicals that could be spilled into the frigid Arctic waters will react to the conditions there--the cold, the water’s salinity, ocean currents altered by weather conditions not seen elsewhere--and how traditional response tools of booms, skimmers, dispersants, and microbes will function in this extreme climate.

Technology maybe the key to a successful response should a spill ever occur. NOAA and the U.S. Coast Guard have partnered in a series of annual simulated spill response exercises to try a variety of new technologies to offset the lack of in-place infrastructure. Among the tools being tested are unmanned aerial aircraft, autonomous underwater vehicles, balloons with cameras, as well as drifter buoys tracked by space satellites. Additionally NOAA, the Coast Guard and regional partners have been working with industry and academia to fill the Arctic ERMA mapping system with advanced scientific based information concerning natural resources, communities and existing infrastructure that could be affected, as well as developing proposed response plan scenarios.