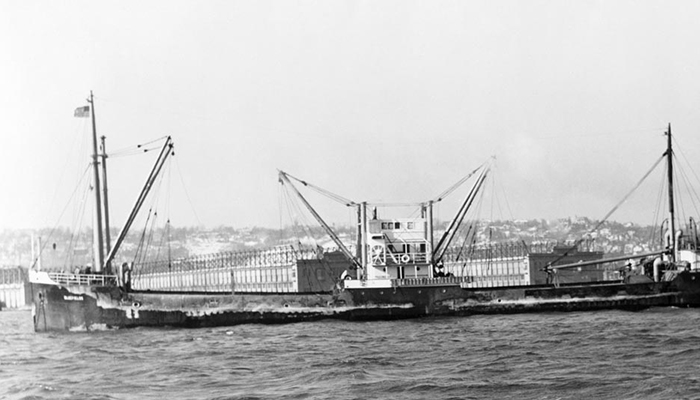

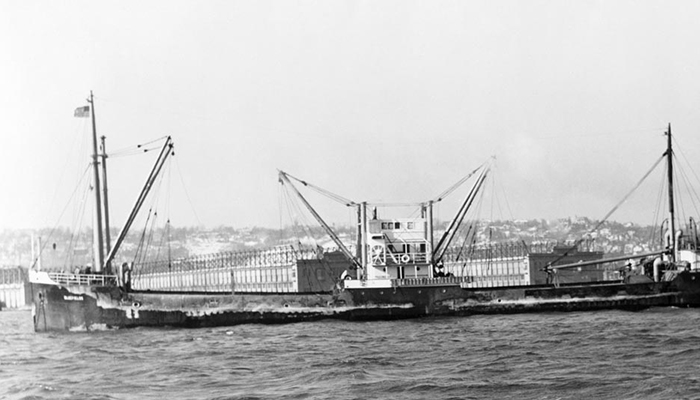

USS Conestoga (AT 54), the last known broadside photograph taken likely during WWI when the tugboat was equipped with a 3-inch 50 caliber naval gun and two machine guns. The tugboat was later equipped with only a single 3-inch 50 caliber gun when it disappeared while en route from Mare Island to America Samoa, by way of Pearl Harbor in 1921. (Image credit: U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command NH 71299)

Science and shipwrecks: Preserving America’s maritime history

Shipwrecks: The stuff of legends

How are shipwrecks discovered?

Safeguarding shipwrecks and other archaeological sites

NOAA Sanctuaries and shipwrecks

The most famous of all wrecks: The Titanic

Shipwrecks are the stuff of epic tales and imagination. Some sank in battle, some in transit. They were war machines, whalers and luxury cruise liners.

Their doomed crew and passengers became legends. Rich and poor, from Gilded Age millionaires luxuriating at sea to sailors and deckhands in service to their country.

Shipwrecks have been honored in story and song through the centuries, from the Edmund Fitzgerald of Gordon Lightfoot’s song to Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner and Melville’s Moby-Dick. Even Shakespeare had his say in The Tempest, when the spirit Ariel sings, “Full fathom five thy father lies,” to the shipwrecked Ferdinand.

About 3,000 ships and submarines of many countries are thought to be sunken in America’s national marine sanctuary waters. NOAA scientists, oceanographers and divers have discovered 400 sites – and they’ve helped find many more.

Where NOAA comes in

When the wreck sites fall in sanctuary waters, NOAA is responsible for preserving and protecting the ships and their artifacts on behalf of our country’s maritime heritage.

Some wrecks still hold the remains of passengers and sailors. Navy wrecks are protected under the Sunken Military Craft Act and foreign vessels are protected under international law as gravesites.

But all sunken ships open a window into another time and another age when ironclads fought, enemy submarines prowled the coasts and cruise ships succumbed to the deep.

Check out more videos from this series from NOAA Ocean Today.

Sometimes, as in the cases of the famous Civil War ironclad USS Monitor off North Carolina, or the USS Bugara, a U.S. Navy submarine that received three battle stars for its service in World War II, we know where shipwrecks are.

5

The number of Allied ships sunk during World War II's Battle of the Atlantic – discovered in a proposed expansion area of the Monitor National Marine Sanctuary that lies off the North Carolina coast.

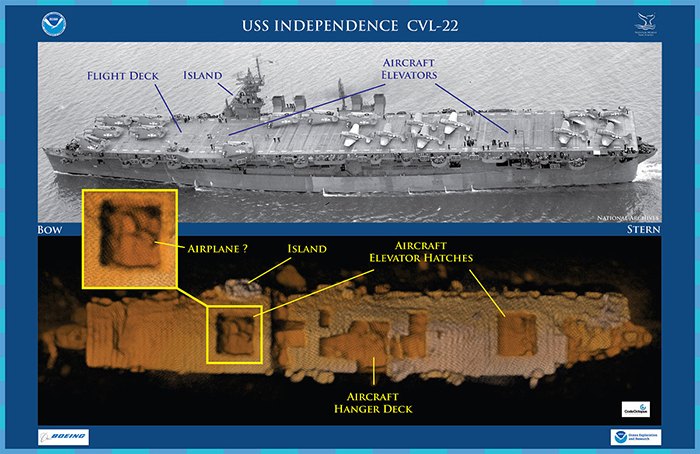

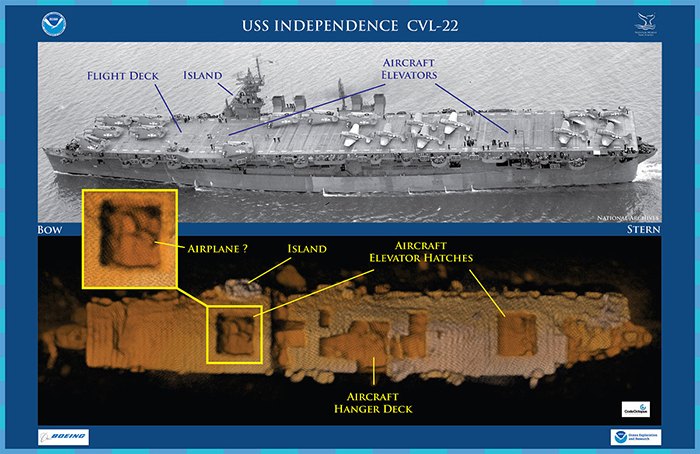

For instance, NOAA, Navy and private industry used a remotely operated vehicle, a kind of underwater robot, to locate the USS Independence, a World War II light aircraft carrier. It was part of a two-year mission to locate, map and study historic shipwrecks in NOAA’s Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary and nearby waters. The carrier is one of an estimated 300 wrecks in the waters off San Francisco, and the deepest known shipwreck in the sanctuary. NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries manages 13 national marine sanctuaries and two marine national monuments, and many of them harbor shipwrecks.

Using seafloor mapping sonars and autonomous underwater vehicles, NOAA ships sometimes spot wrecks when they’re surveying the ocean floor for other missions, or collecting other scientific data. Fishermen may hit something on the bottom with their gear or a diver may encounter an undiscovered wreck while exploring an area.

Once a shipwreck is located, historians and maritime archaeologists enter the scene usually by a remotely operated vehicle or ROV, cataloging but not removing artifacts, and putting them into perspective so we can understand what life was like for these sailors.

Shipwrecks are time machines that take us back to the days of Spanish galleons and the age of steamboats, from the conflicts from the Civil War to the battles of World War II. Through its sanctuaries, NOAA is responsible for locating, assessing, protecting, managing, and interpreting the nation’s maritime heritage resources – including shipwrecks.

240 yards

The distance between the wrecks of German U-boat U-576 and the Nicaraguan-flagged freighter SS Bluefields, which the U-boat sunk off North Carolina in 1942.

The National Marine Sanctuaries Act makes it illegal to disturb a site or recover artifacts within a national marine sanctuary without a permit. Only under very specific circumstances does the sanctuary issue a permit for the planned recovery of artifacts in accordance with the federal laws. Some possible reasons for recovering artifacts include protecting them from harsh environmental conditions and looting; conducting research that includes public education; making artifacts more available to the public through museum partnerships; and improving scientific understanding of the sanctuary.

NOAA protects shipwrecks for other reasons as well. Sometimes, the sunken vessels scattered across the U.S. seafloor could pose an oil pollution threat. Many 20th-century wrecks still have their fuel tanks and possible pollutants intact. Containing those pollutants protects the sanctuary and its ecosystem.

Since 2010, NOAA's Office of Response and Restoration and Office of National Marine Sanctuaries, working with the U.S. Coast Guard, have been looking at which of these wrecks might pose a substantial threat of leaking oil still on board. This work is part of NOAA's Remediation of Underwater Legacy Environmental Threats (RULET) project.

And some wrecks of foreign ships are protected under Sunken Military Craft Act or treaties, such as the U-576, a German World War II U-boat sunk off North Carolina near a NOAA sanctuary with its crew, now considered a war grave.

NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries manages 13 national marine sanctuaries and two marine national monuments. Among the coral, the dolphins, the sea lions and other treasures in the more than 600,000 square miles of protected waters lie shipwrecks. In fact, some sanctuaries are built around them.

Take the Monitor National Marine Sanctuary off the coast of North Carolina, NOAA’s first marine sanctuary. It’s named for one of the most famous shipwrecks in American history, the Civil War-era USS Monitor offsite link.

Near the sanctuary’s boundaries is the first ship sunk by a German U-boat off North Carolina's coast, the steam tanker Allan Jackson that was torpedoed by the U-66, 60 miles east-northeast of Diamond Shoals. NOAA has proposed expanding the sanctuary to include some nearby wreck sites.

41

Known shipwrecks in NOAA’s proposed Wisconsin-Lake Michigan national marine sanctuary. The sanctuary’s shipwrecks date back to the 19th and early 20th centuries.

More than 400 reported ship and aircraft wrecks may exist in the Greater Farallones sanctuary off central California, from a 16th-century Spanish galleon to the 19th century Ayacucho, a brigantine in the coastal trade described by author Richard Henry Dana in Two Years Before the Mast.

One of NOAA’s sanctuaries, Thunder Bay, contains shipwrecks that represent a cross-section of Great Lakes maritime history. The cold, fresh waters of Lake Huron have provided a favorable environment for shipwreck preservation, though waves and ice have damaged some shallow wrecks.

A NOAA-led expedition to study marine archaeology in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands found the wreck of Two Brothers, a New England-based whaler captained by George Pollard. Pollard captained doomed whaler Essex, whose story of drifting on the open ocean and cannibalism found its way to Herman Melville, who used the incident as fodder for his classic novel, Moby-Dick. The wreck was found 600 miles northwest of Honolulu, in Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument.

On subsequent dives, researchers also found some of the Two Brothers equipment – blubber hooks, harpoon tips, lances, and cooking pots. The wreck site was recently added to the National Register of Historic Places, the official list of the nation's sites worthy of preservation.

Mallows Bay is most renowned for the remains of more than 100 wooden steamships, known as the "Ghost Fleet," which were built for the U.S. Emergency Fleet from 1917 to 1919 as part of America’s engagement in World War I. Their construction at more than 40 shipyards in 17 states reflected the massive national wartime effort that drove the expansion and economic development of communities and related maritime service industries.

It was built in Belfast, the largest ship of its kind ever constructed. When it left Southampton on April 10, 1912, the RMS Titanic’s New York-bound passengers included some of the wealthiest and well-known people in the world. The band played “The White Star Line March” as an estimated 2,224 men, women and children boarded the ship unaware that in five days, their lives would be changed forever.

The wreck of the Titanic does not lie in a NOAA sanctuary. It was first discovered in 1985, off the coast of Newfoundland, in an expedition co-led by Robert Ballard offsite link, an explorer with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution offsite link, a frequent NOAA partner. The ship was split in two and lies at more than 12,000 feet beneath the sea.

Since the discovery, NOAA's Office of Ocean Exploration and Research has conducted two field expeditions to the wreck site. NOAA sponsored an 11-day research cruise in June 2003 with two three-person submersibles capable of diving to depths of 6,000 meters, much deeper than the wreck site.

Three NOAA scientists lead the expedition, along with two archaeologists from the National Park Service, one who had worked on the USS Arizona memorial in Pearl Harbor. Scientists also looked at microbial communities called rusticles, that consumed much of Titanic’s iron and cling to the wreck like rusty icicles.

In 2004, nearly 20 years after first finding the sunken remains of the RMS Titanic, Ballard returned to help NOAA study the ship's rapid deterioration.

The team spent 11 days at the site, mapping the ship and conducting scientific analyses of its deterioration from aboard the NOAA Ship Ronald H. Brown. Scientists used remotely operated vehicles to document the Titanic in a way that was not possible in the 1980s. And still plainly in sight on the ocean floor were shoes, bottles and the remnants of the dome of the ship’s grand staircase, artifacts still recognizable more than 100 years later.

£870

Cost in 1912 British pounds, about $110,000 today, of a parlor suite on the Titanic.

In 2012, the 100th anniversary year of the ship’s sinking, NOAA again addressed the fate of the fabled ship. Along with the National Park Service, the U.S. Coast Guard, and the International Maritime Organization, NOAA advised all vessels to not dump any trash or other waste in a zone approximately 10 square nautical miles above the wreck. Further, the International Maritime Organization requested submersible vehicles keep away from the Titanic's deck, and divers to refrain from placing plaques or other permanent memorials on the wreck.

Shipwrecks are the stuff of epic tales and imagination. Some sank in battle, some in transit. They were war machines, whalers and luxury cruise liners.

Their doomed crew and passengers became legends. Rich and poor, from Gilded Age millionaires luxuriating at sea to sailors and deckhands in service to their country.

Shipwrecks have been honored in story and song through the centuries, from the Edmund Fitzgerald of Gordon Lightfoot’s song to Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner and Melville’s Moby-Dick. Even Shakespeare had his say in The Tempest, when the spirit Ariel sings, “Full fathom five thy father lies,” to the shipwrecked Ferdinand.

About 3,000 ships and submarines of many countries are thought to be sunken in America’s national marine sanctuary waters. NOAA scientists, oceanographers and divers have discovered 400 sites – and they’ve helped find many more.

Where NOAA comes in

When the wreck sites fall in sanctuary waters, NOAA is responsible for preserving and protecting the ships and their artifacts on behalf of our country’s maritime heritage.

Some wrecks still hold the remains of passengers and sailors. Navy wrecks are protected under the Sunken Military Craft Act and foreign vessels are protected under international law as gravesites.

But all sunken ships open a window into another time and another age when ironclads fought, enemy submarines prowled the coasts and cruise ships succumbed to the deep.

Check out more videos from this series from NOAA Ocean Today.

Sometimes, as in the cases of the famous Civil War ironclad USS Monitor off North Carolina, or the USS Bugara, a U.S. Navy submarine that received three battle stars for its service in World War II, we know where shipwrecks are.

5

The number of Allied ships sunk during World War II's Battle of the Atlantic – discovered in a proposed expansion area of the Monitor National Marine Sanctuary that lies off the North Carolina coast.

For instance, NOAA, Navy and private industry used a remotely operated vehicle, a kind of underwater robot, to locate the USS Independence, a World War II light aircraft carrier. It was part of a two-year mission to locate, map and study historic shipwrecks in NOAA’s Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary and nearby waters. The carrier is one of an estimated 300 wrecks in the waters off San Francisco, and the deepest known shipwreck in the sanctuary. NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries manages 13 national marine sanctuaries and two marine national monuments, and many of them harbor shipwrecks.

Using seafloor mapping sonars and autonomous underwater vehicles, NOAA ships sometimes spot wrecks when they’re surveying the ocean floor for other missions, or collecting other scientific data. Fishermen may hit something on the bottom with their gear or a diver may encounter an undiscovered wreck while exploring an area.

Once a shipwreck is located, historians and maritime archaeologists enter the scene usually by a remotely operated vehicle or ROV, cataloging but not removing artifacts, and putting them into perspective so we can understand what life was like for these sailors.

Shipwrecks are time machines that take us back to the days of Spanish galleons and the age of steamboats, from the conflicts from the Civil War to the battles of World War II. Through its sanctuaries, NOAA is responsible for locating, assessing, protecting, managing, and interpreting the nation’s maritime heritage resources – including shipwrecks.

240 yards

The distance between the wrecks of German U-boat U-576 and the Nicaraguan-flagged freighter SS Bluefields, which the U-boat sunk off North Carolina in 1942.

The National Marine Sanctuaries Act makes it illegal to disturb a site or recover artifacts within a national marine sanctuary without a permit. Only under very specific circumstances does the sanctuary issue a permit for the planned recovery of artifacts in accordance with the federal laws. Some possible reasons for recovering artifacts include protecting them from harsh environmental conditions and looting; conducting research that includes public education; making artifacts more available to the public through museum partnerships; and improving scientific understanding of the sanctuary.

NOAA protects shipwrecks for other reasons as well. Sometimes, the sunken vessels scattered across the U.S. seafloor could pose an oil pollution threat. Many 20th-century wrecks still have their fuel tanks and possible pollutants intact. Containing those pollutants protects the sanctuary and its ecosystem.

Since 2010, NOAA's Office of Response and Restoration and Office of National Marine Sanctuaries, working with the U.S. Coast Guard, have been looking at which of these wrecks might pose a substantial threat of leaking oil still on board. This work is part of NOAA's Remediation of Underwater Legacy Environmental Threats (RULET) project.

And some wrecks of foreign ships are protected under Sunken Military Craft Act or treaties, such as the U-576, a German World War II U-boat sunk off North Carolina near a NOAA sanctuary with its crew, now considered a war grave.

NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries manages 13 national marine sanctuaries and two marine national monuments. Among the coral, the dolphins, the sea lions and other treasures in the more than 600,000 square miles of protected waters lie shipwrecks. In fact, some sanctuaries are built around them.

Take the Monitor National Marine Sanctuary off the coast of North Carolina, NOAA’s first marine sanctuary. It’s named for one of the most famous shipwrecks in American history, the Civil War-era USS Monitor offsite link.

Near the sanctuary’s boundaries is the first ship sunk by a German U-boat off North Carolina's coast, the steam tanker Allan Jackson that was torpedoed by the U-66, 60 miles east-northeast of Diamond Shoals. NOAA has proposed expanding the sanctuary to include some nearby wreck sites.

41

Known shipwrecks in NOAA’s proposed Wisconsin-Lake Michigan national marine sanctuary. The sanctuary’s shipwrecks date back to the 19th and early 20th centuries.

More than 400 reported ship and aircraft wrecks may exist in the Greater Farallones sanctuary off central California, from a 16th-century Spanish galleon to the 19th century Ayacucho, a brigantine in the coastal trade described by author Richard Henry Dana in Two Years Before the Mast.

One of NOAA’s sanctuaries, Thunder Bay, contains shipwrecks that represent a cross-section of Great Lakes maritime history. The cold, fresh waters of Lake Huron have provided a favorable environment for shipwreck preservation, though waves and ice have damaged some shallow wrecks.

A NOAA-led expedition to study marine archaeology in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands found the wreck of Two Brothers, a New England-based whaler captained by George Pollard. Pollard captained doomed whaler Essex, whose story of drifting on the open ocean and cannibalism found its way to Herman Melville, who used the incident as fodder for his classic novel, Moby-Dick. The wreck was found 600 miles northwest of Honolulu, in Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument.

On subsequent dives, researchers also found some of the Two Brothers equipment – blubber hooks, harpoon tips, lances, and cooking pots. The wreck site was recently added to the National Register of Historic Places, the official list of the nation's sites worthy of preservation.

Mallows Bay is most renowned for the remains of more than 100 wooden steamships, known as the "Ghost Fleet," which were built for the U.S. Emergency Fleet from 1917 to 1919 as part of America’s engagement in World War I. Their construction at more than 40 shipyards in 17 states reflected the massive national wartime effort that drove the expansion and economic development of communities and related maritime service industries.

It was built in Belfast, the largest ship of its kind ever constructed. When it left Southampton on April 10, 1912, the RMS Titanic’s New York-bound passengers included some of the wealthiest and well-known people in the world. The band played “The White Star Line March” as an estimated 2,224 men, women and children boarded the ship unaware that in five days, their lives would be changed forever.

The wreck of the Titanic does not lie in a NOAA sanctuary. It was first discovered in 1985, off the coast of Newfoundland, in an expedition co-led by Robert Ballard offsite link, an explorer with the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution offsite link, a frequent NOAA partner. The ship was split in two and lies at more than 12,000 feet beneath the sea.

Since the discovery, NOAA's Office of Ocean Exploration and Research has conducted two field expeditions to the wreck site. NOAA sponsored an 11-day research cruise in June 2003 with two three-person submersibles capable of diving to depths of 6,000 meters, much deeper than the wreck site.

Three NOAA scientists lead the expedition, along with two archaeologists from the National Park Service, one who had worked on the USS Arizona memorial in Pearl Harbor. Scientists also looked at microbial communities called rusticles, that consumed much of Titanic’s iron and cling to the wreck like rusty icicles.

In 2004, nearly 20 years after first finding the sunken remains of the RMS Titanic, Ballard returned to help NOAA study the ship's rapid deterioration.

The team spent 11 days at the site, mapping the ship and conducting scientific analyses of its deterioration from aboard the NOAA Ship Ronald H. Brown. Scientists used remotely operated vehicles to document the Titanic in a way that was not possible in the 1980s. And still plainly in sight on the ocean floor were shoes, bottles and the remnants of the dome of the ship’s grand staircase, artifacts still recognizable more than 100 years later.

£870

Cost in 1912 British pounds, about $110,000 today, of a parlor suite on the Titanic.

In 2012, the 100th anniversary year of the ship’s sinking, NOAA again addressed the fate of the fabled ship. Along with the National Park Service, the U.S. Coast Guard, and the International Maritime Organization, NOAA advised all vessels to not dump any trash or other waste in a zone approximately 10 square nautical miles above the wreck. Further, the International Maritime Organization requested submersible vehicles keep away from the Titanic's deck, and divers to refrain from placing plaques or other permanent memorials on the wreck.