Scientists in the U.S. Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico employ state-of-the-art technologies

NOAA Ship Nancy Foster. (Image credit: NOAA)

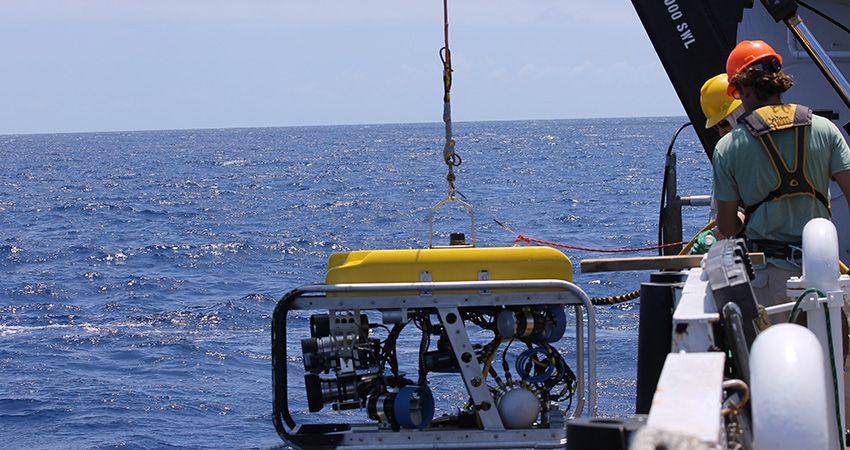

Splashdown! The remotely operated vehicle, or ROV, enters the water suspended from a crane on the 187-foot NOAA research vessel Nancy Foster, a few miles offshore in the U.S. Virgin Islands. “Go, go, go,” the tending crew member says into his radio, as he lets out the ROV’s electrical umbilical cable that tethers it to the ship.

Hearing the command, the ROV operator sitting inside a darkened workroom on the ship starts steering the ROV as it descends. The coral reefs it will soon explore range from 10 to several hundred meters deep.

This is what scientific exploration looks like in the 21st century.

The reefs and their fish populations around the U.S. Virgin Islands – and neighboring Puerto Rico – have long needed thorough study so that they could be better managed and protected.

After several minutes of descent into the water, the ROV hovers a few meters above the reef. A set of monitors allow scientists on board the Nancy Foster to see and record everything the ROV cameras see. The operator radios the ship’s bridge that they are ready to follow a preplanned path over the reef.

On the bridge, the watch officer punches in some commands to the ship’s computer-controlled system that has been holding it still in an exact spot. With the new commands, the autopilot now slowly and smoothly moves the Nancy Foster along the planned path in defiance of the wind and current. Such precision ship control, and a bit of slack in the umbilical cable, gives the ROV a few minutes to explore an area of the reef as both ship and ROV travel as a pair.

Meanwhile inside the ship’s workroom, warm and dry, NOAA oceanographer Tim Battista busily snaps still photos as the ROV operator pans and zooms the camera on corals, fish and other features of the reef.

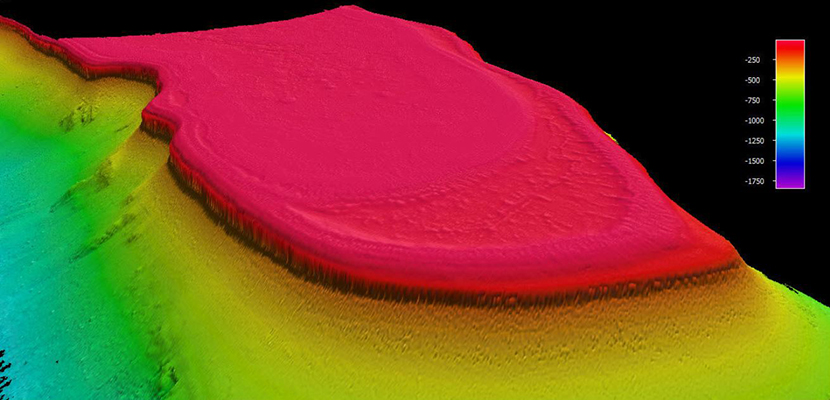

Battista has another technology at his disposal: The night before, the Nancy Foster mapped the reef in wide swaths using mulitbeam sonar. This type of sonar sends hundreds of sound beams that reflect off the reef and back to a receiver on the ship. All of those individual reflections gather vast amounts of data that form a map of the features, depth variations and complexity of the reef.

“The sonar mapping gives you lots of data, but it’s difficult to tell what it is,” says Battista. “It’s like a sonogram – you have to be an expert to know what you’re looking at.

“After mapping at night, we send down the ROV during daylight at selected areas on the map. This way, we get photos and video to go with all that sonar data, giving us a more complete understanding of the coral and fish that call the reef home.”

With the project now in its 13th year, the knowledge gap in what NOAA scientists know about Caribbean coral reefs is shrinking. Data and imagery gathered using high-tech tools are making it easier to protect the reefs and help ensure that fish populations remain healthy and abundant.