From Alaska to Maine, undergraduates got their feet wet while interning at National Estuarine Research Reserves. Estuaries, where rivers meet the sea, are constantly in flux. In these productive ecosystems, you never know what you'll find — or what you're going to learn. From the inspiring to the unexpected, 12 undergraduate scholars share what surprised them most about spending a summer in an estuary.

To celebrate National Estuaries Week, September 14-21, 2019, we are featuring the stories of NOAA Hollings scholars who interned at nine different National Estuarine Research Reserves (NERRs) around the country. Learn more about NERRs.

Kachemak Reserve

Katie Hearther

Katie Hearther spent her summer in Alaska at the Kachemak Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve (KBNERR). Her project involved working with the educational team and the Coastal Training Coordinator at KBNERR to restructure their procedures for conducting field-based learning experiences. Hearther wanted to choose a project involved in environmental education because she “firmly believes that even the best, most concrete science has little impact if you cannot successfully communicate its meaning to decision-makers.”

What surprised you about working in an estuary?

“From a natural science perspective, I was completely oblivious to how essential salt marshes, peat bogs, and headwaters are to the salmon populations in Alaska. The most surprising thing to me was how incredibly dedicated and motivated the reserve staff was in everything they did, including their support for their interns. I was interested in the social science behind environmental education before heading into this internship but possessed little knowledge or practical experience. The education and training staff welcomed me with open arms and proceeded to blow my mind with how many meaningful connections they have with other environmental educators and organizations. I came to Alaska because I was fascinated by the natural science, but will ultimately return because of the kindness and tenacity of the people.”

Andrew Tokuda

Andrew Tokuda also interned at the Kachemak Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve (KBNERR) in Alaska this summer. Tokuda aspires to join the U.S Army as an active-duty officer with the dream of improving the dialogue between the military and environmental sciences, so he wanted an internship that would encompass both terrestrial and marine environments. His project focused on characterizing riparian prey availability for juvenile salmon in the Anchor River estuary on the Kenai Peninsula.

What surprised you about working in an estuary?

“I was personally surprised to discover how estuaries play such a critical role in the life-cycles of Alaskan fish, many of which are commercially valuable. Estuarine systems can also be quite vulnerable. Damaging one can have numerous implications in terms of ecosystem health, and this can affect local communities that rely on it. What made my experience in Alaska truly unique was also the fact that I got to participate in other researchers’ projects in a variety of scientific areas, which painted an overall picture of the ongoing research done at Kachemak Bay. Overall, I am beyond grateful to have been able to work with a family of such passionate and knowledgeable researchers, as well as being able to socialize with the local community, and further realizing that both had a common mindset of taking care of the environment for future generations.”

He‘eia Reserve

Diana Lopera

Diana Lopera spent her summer conducting research in Hawaii at the He‘eia National Estuarine Research Reserve (HeNERR). Lopera’s project involved conducting pre- and post-surveys of water circulation and flow before and after invasive macroalgae was removed from Loko i’a o He’eia, or the traditional Native Hawaiian He’eia fishpond.

What surprised you about working in an estuary?

“What surprised me about my work at HeNERR this summer is how much [this experience] impacted the direction of where I want to go in my career journey. I really enjoyed talking and working directly with the caretakers of the fishpond and communicating the research I do and why I am doing it. It has made me realize that I don’t want to just do research, I want to be part of that next step in making sure the research I do is made clear and is applied the best way it can to whoever may need it.”

South Slough Reserve

Madison Bowe

Madison Bowe conducted her internship at the South Slough National Estuarine Reserve in Oregon. Her project focused on explaining the variation in accretion rates at the sentinel site marshes in South Slough. Bowe learned about the complex interactions which drive accretion rates in the marshes, and also discovered that she “definitely wants to work and live on the West Coast in the future.”

What surprised you about working in an estuary?

“What surprised me most about working in an estuary was the variety of science which happens at this reserve. One day we were counting marsh plants and measuring sediment accretion, the next we were out on a boat fish-seining for an eDNA project, then monitoring endangered western lilies in the forest. This reserve supports a lot of interesting projects, and I got great experience with a variety of fieldwork [techniques].”

Lake Superior Reserve

Risa Askerooth

Risa Askerooth spent her summer in Wisconsin at the Lake Superior National Estuarine Research Reserve. Askerooth’s work involved evaluating the success of a wood waste removal restoration in the St. Louis River Estuary, a wetland region listed as an Area of Concern. Having grown up around the Pacific Ocean, the massive amount of freshwater in the Great Lakes region has always fascinated her, and she was excited to be a small part of the effort to support the delisting of the estuary as an Area of Concern this summer.

What surprised you about working in an estuary?

“Having lived all my life near the ocean, I am always surprised after a day out on the boat that my hair isn't crunchy from all the salt spray — since it's all freshwater here! I was surprised at the diversity of habitats within the estuary; from the mouth of Lake Superior to upstream areas, the size of the river and the organisms that live in it change drastically!”

Old Woman Creek Reserve

Osanna Drake

Osanna Drake conducted her internship at Old Woman Creek (OWC) National Estuarine Research Reserve in Ohio. Her project focused on increasing the utility, sustainability, and scientific rigor of OWC’s species monitoring program through the development and implementation of effective data management practices, visual information products, and targeted field work.

What surprised you about working in an estuary?

“Perhaps the biggest surprise was the dedication of our volunteers. These are people who care so much about the estuary and our research that they will go out at all hours of the day and in harsh conditions just to collect our monitoring data. Some have been helping the program for over four years and still approach us regularly to ask how they improve their efforts. They take their work more seriously than some professionals I’ve met, despite not being paid a dime. Working with community members who care so deeply about what they do, and who want their hard work to mean something, motivated me in my endeavors and gave me hope for the future.”

Apalachicola Reserve

Savannah Weber

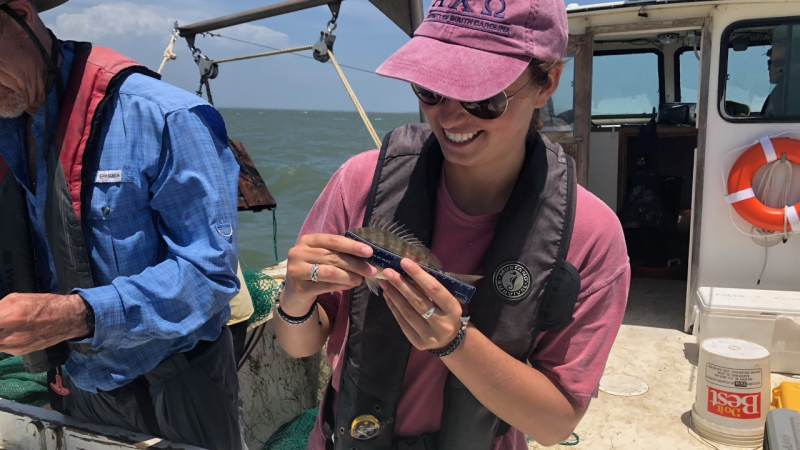

Savannah Weber spent her summer internship in Florida at the Apalachicola National Estuarine Research Reserve. Weber focused on the effects of long-term fishery trawling, specifically studying the distribution of white shrimp in the Apalachicola Bay, to understand how different environmental factors can affect a population.

What surprised you about working in an estuary?

“This summer I was surprised to find how much I enjoyed field work and research. Though each field day I would come back drenched in sweat, sand, and fish scales, I still absolutely loved every experience! I was also able to strengthen my analytical skills and deepen my understanding of population dynamics, especially in estuary systems.”

Chesapeake Bay - Virginia Reserve

Stephanie Letourneau

Stephanie Letourneau chose to intern at the Chesapeake Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve in Virginia (CBNERR-VA). Letourneau created and piloted traditional and digital lesson plans for students based on the current NERRs thin-layer placement project offsite link, and received valuable feedback from teachers on which platform was more useful. She also created the first story map for CBNERR-VA to help educators effectively teach science while using technology.

What surprised you about working in an estuary?

“I was surprised by how many new skills and research techniques I learned. Before this summer, I knew nothing about evaluation of educational resources and about long-term monitoring in an estuary. I was also surprised at how much I would enjoy learning and teaching about them and getting dirty in the mud to collect data. It was rewarding to take a topic I did not know much about, become an expert, and help others understand the importance, too. Watching students enjoy and interact with my lesson was the highlight of my summer.”

Waquoit Bay Reserve

Sophia Courtney

Sophia Courtney spent her summer in Massachusetts at the Waquoit Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve. Courtney studied the influence of burrowing crabs on salt marsh substrate stability and vegetation, a project that directly involved several of her research interests: plant-animal interactions, biogeochemistry, conservation, and climate change.

What surprised you about working in an estuary?

“My favorite part about working in an estuary was getting to be out in the marsh where I could observe changes everyday. Over the course of two months, different plants sprouted, bloomed, went to seed, and died back. I watched the tides come up and down, and learned at what time of day the marsh crabs are active and when the flies come out. Doing consistent field work really gave me an intimate understanding of my beautiful study site, and led me to think of more questions for potential future research.”

Wells Reserve

Megan Gillen

Megan Gillen was one of three Hollings scholars who conducted their internships at the Wells National Estuarine Research Reserve in Maine. She characterized salt pools in the Little River marsh at the reserve and analyzed recent changes in their size, abundance, and other physical properties. Gillen noted that her project was the “perfect harmony of all of her interests, combining field-based data collection with remote sensing.”

What surprised you about working in an estuary?

“I had some previous experience working with marshes in an estuary, but this internship was nothing like I expected. The wetlands at the Wells Reserve are massive (nearly 1,500 acres!) and experience an astounding 10-foot tidal range. Being able to work in this unique environment reinforced my passion for studying and researching estuaries!”

Kayla Rexroth

Also at the Wells National Estuarine Research Reserve in Maine, Kayla Rexroth dove into multiple projects during her summer internship. Her main project involved extracting eDNA offsite link from green crabs and their surrounding aquatic environment. Rexroth intends to conduct research using eDNA to track the migration patterns of endangered species, ideally elasmobranchs, in the future.

What surprised you about working in an estuary?

“Actually, the most interesting discovery with this project was the fact that the sediment samples consistently contained higher concentrations of eDNA than the water samples. It will be interesting to try and replicate this experiment in the estuary when it experiences a daily tidal cycle of 10 to 11 feet, sometimes fully exposing the sediment at the bottom. Overall, this has been an amazing experience and I could not be more grateful for gaining the opportunity to work with some amazing scientists at such an amazing organization.”

Sophia Troeh

Sophia Troeh also interned at the Wells National Estuarine Research Reserve in Maine. Troeh has always been interested in science confidence and how young people perceive scientists. She thought a reserve would be the perfect place to study these topics, as reserves combine both research and education in one setting. Her internship involved surveying campers ages 5-14 before and after camp to analyze their change in enjoyment in outdoor activity, science confidence, and interest in science-related careers.

What surprised you about working in an estuary?

“I was surprised by the campers’ abilities to absorb information and their genuine interest in the subject matter. If everyone was as open-minded and curious about the natural world as these campers, nature would certainly be more appreciated worldwide. As for my career goals, I hope to go into outdoor or environmental education and outreach, hoping to inspire conservation and enthusiasm for nature and science in the next generation.”