Through federal funding opportunities of up to $5,000, NOAA Planet Stewards supports educators in leading hands-on, action-based projects that conserve, restore, and protect human communities and natural resources from environmental challenges.

In fiscal year 2022, 6,658 students, educators, partners, and families engaged in 84,377 hours of stewardship project education and implementation in California, Florida, Hawaiʻi, Kentucky, Maryland, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, and Texas. Projects involved habitat restoration, carbon sequestration, marine debris, and invasive species removal.

This year, we’re highlighting Planet Stewards educators who worked with their students to lead habitat restoration projects. In addition to adding vital native habitat and sequestering carbon, these projects had aesthetic, social, and academic benefits. Students worked with experts in their communities and explored their restoration projects through an interdisciplinary lens.

Student-designed gardens in Florida

Seminole High School in Florida is a 64-acre campus that had what advanced studies teacher Jerry Cantrell described as “minimal vegetation on it.” With funding from NOAA Planet Stewards, Cantrell empowered students to cultivate 11 new areas for native plants, totaling approximately 6 acres. Students took on the process of designing, creating, and maintaining natural gardens with expert assistance from community and university partners. “Our environmental awareness project is enabling students to take ownership in designing, creating, and maintaining natural gardens around [Seminole High School],” said Cantrell. “Students have an opportunity to earn service hours … and become leaders within the school community.”

During the planning process, students considered the educational, social, and emotional role that these spaces for native plants would have for the student body. The students planted multiple gardens: a memorial garden, a student-centered meeting space, area improvement gardens in front of the school, shade gardens near the school’s auditorium, as well as clearing and updating a vegetable garden, and small beautification gardens in teacher areas. Future plans include a butterfly garden and aquaponics (in which fish and plants are cultivated together).

In addition to providing nectar, pollen, and seeds that are important food sources for regional species of butterflies, insects, birds, and other animals, these native plant gardens have become hubs for interdisciplinary exploration. Students learn about life cycles in biology, do writing exercises in language arts to reflect on nature, prepare garden information in foreign languages, and apply sustainable engineering practices. Based on EcoMatcher’s carbon sequestration formula offsite link, the carbon dioxide sequestered this year is 13,408 lbs.

Native Youth Science Club restores pollinator habitat

Amelia Cook, science teacher at Norman High School in Oklahoma, worked with students in the Native Youth Science Club to sequester carbon while developing a native pollinator garden. The Tribal Alliance of Pollinators, the South-Central Climate Adaptation Science Center, and the Chickasaw Nation collaborated with middle and high school students to design the garden space and donated native plant species. Cook was inspired by the concept of “two-eyed seeing.” “Two-eyed seeing is a Mi'kmaw principle that refers to seeing the strengths of Indigenous ways of knowing with one eye, and from the other, the strengths of Western ways of knowing, and learning to use both eyes together for the benefit of all,” she explained.

Approximately 50 sixth through 12th grade students restored 100 square feet of pollinator habitat. Although the area was small, it has had an outsized effect on both species diversity and campus appreciation. By surveying species before and after the habitat restoration, students found that species diversity increased from two plant species to 15 species and from two animal species to six — a 650% increase in plant biodiversity and a 200% increase in animal diversity. “The plant species are pretty and have attracted a lot of attention from parents waiting to pick up their child in the parking lot,” said Cook. “There were many conversations with parents and students not involved in the project about endangered pollinators, habitat restoration, native plants, and how to adapt to our changing ecosystem. We are very proud of the beds!”

Cook was pleased that this project provided an opportunity for the school community to embrace Indigenous science. “Native and non-Native students and adult volunteers were involved in this project and experienced Indigenous Science education together. There were many conversations about our ecological footprints, our understanding and connection to the ecosystem, and how we can heal our human and non-human relationships to build stronger communities,” she said.

Reducing runoff in Lexington

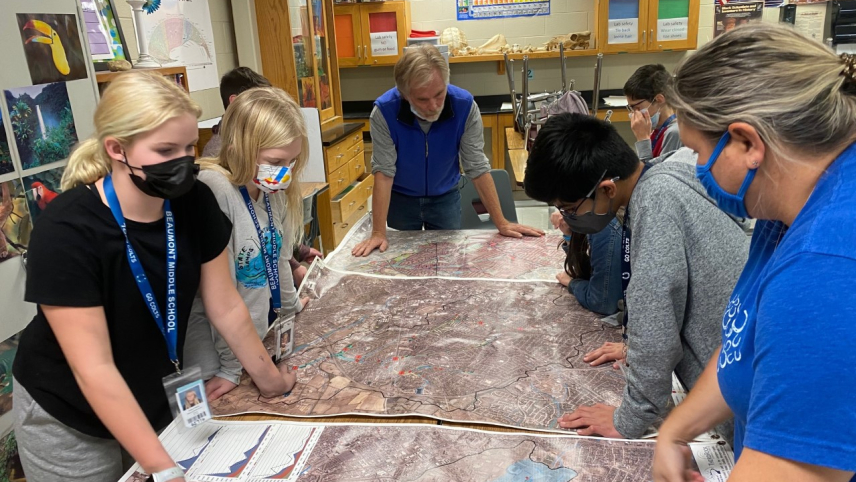

Because of persistent issues with the city’s sanitary and storm sewer system, the Environmental Protection Agency has determined that Lexington, Kentucky, violates the Clean Water Act during heavy rains. To help reduce the strain on Lexington’s overtaxed sewer system, science teacher Patrick Geoff and his students at Beaumont Middle School led a project to build a rain garden that allows the water that flows off the school’s parking lot to be absorbed into the ground locally.

“This diversion allows the rainfall that has various pollutants, many from the 50-plus vehicles that park on the parking lot, to be absorbed by the ground prior to entering the Wolf Run watershed,” said Geoff. “By catching the outflow from the parking lot that would have any fluids that leaked out of the various vehicles and trapping it, it allows Wolf Run a chance to run cleaner, which in turn keeps the next waterway a little cleaner.”

Geoff and 35 students increased their rain garden system by approximately 980 square feet, which in turn allowed for 980 cubic feet of storm water runoff to be held and absorbed instead of entering the stormwater system. Their secondary goal was to create a habitat for butterflies and pollinators in the local community. “Any chance we can get to help our pollinators out is one that needs to be taken,” said Geoff. The school now has a Rain Garden Club that will continue supporting this project. “This outcome was of great pride for me because we were able to get 6th grade students to take interest and ownership in our rain gardens.”

More trees in ‘Tree City,’ Ohio

Trees are a source of pride for Defiance City, Ohio. The city was recognized as a 2020 Tree City USA offsite link and received a Growth Award from the Arbor Day Foundation because of its commitment to effective urban forest management. Julie Houck, third grade teacher at Defiance Elementary School, and her students have embraced this local identity by planting 120 more trees in their hometown.

More than 600 elementary students from four local counties were involved in trees at two sites: Lily Creek Farms, a therapeutic riding center with a nature trail that had trees die along its path, and a nature preserve, which also has an outdoor classroom and offers a summer nature camp. Many community partners were involved, including researchers from the Global Learning and Observation to Benefit the Environment (GLOBE) Program, a worldwide citizen science network for students. GLOBE researchers spoke with students about their careers, and students contributed data on trees to the GLOBE Observer App.

Houck reported that this project absorbed 1,322 pounds of carbon in its first year, a contribution that will continue to grow along with the trees. Once the trees are fully grown, they will remove 5,555 pounds of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere each year, sequestering more than 100 tons of carbon over 40 years. Houck and her students are proud of the legacy this project will have. “It brings about civic pride, and generations to come will have better quality of life because of the work that we do today to plant trees!” said Houck.

Restoring wetlands along the Rio Grande

The Border Region of West Texas, Southern New Mexico, and Northern Chihuahua faces a variety of threats, including habitat loss, deterioration of freshwater resources, and climate change. Working in partnership with the Rio Bosque Wetlands Park, high school students participated in the Young Stewards Promoting Border Resiliency project to restore one acre of riparian wetland habitat adjacent to the Rio Grande River in El Paso, Texas.

“Wetlands and riverside forests once dominated the banks of the Rio Grande in the Border Region,” explained Jennifer Ramos-Chavez, an educator at Insights El Paso Science Discovery, Inc. “They were the most productive natural habitats in the region, but today they are virtually gone as a result of channeling and damming the Rio Grande River, land conversion, and border fence building.”

With the help of high school students, a restoration manager, an aquatic scientist and environmental scientist, the Young Stewards Promoting Border Resiliency project removed 65.2 cubic meters of invasive plant biomass, planted 72 native shrubs and trees, and seeded three dozen native wetland plants. This project involved 40 high school students and 15 graduate students from the University of Texas at El Paso who served as volunteers and mentors. Combined, they contributed nearly 1,200 hours of stewardship activities.

“Despite carrying out this project in the midst of a pandemic, we were able to work with and inspire students from the El Paso Border Region, majority of whom are from underrepresented groups,” said Ramos-Chavez. “We have been able to expose them to topics and issues that are relevant to the environment they live in, share STEM career pathways by individuals that practice those careers locally, and most importantly have given these students a sense of responsibility and initiative to make real life changes that will benefit the global environment.”

A tiny forest in Portland

With funding from NOAA Planet Stewards, students at Catlin Gabel School in Portland, Oregon, have created a “tiny forest” on campus. This densely planted ecosystem, no larger than a tennis court, will provide an opportunity for pre-K through 12th grade students to study soil biology, track tons of sequestered carbon, and survey native plant and animal species.

Between drought, extreme heat, and wildfire, climate change is a source of concern for Oregon residents. “There is a lot of climate anxiety, and in conversation with students I often hear hopelessness,” said teacher Patrick Walsh, who anticipates that the tiny forest will be a source of hope and resiliency for the school community. “Students will watch the forest grow through their years at the school, cultivating stewardship as they learn about climate change and biodiversity,” said Walsh.

Approximately 175 people participated in the planting day in 2021. “Students, parents, teachers, administrators, staff members, people from every part of our school came together and worked happily in shifts throughout the day,” said Walsh. Since then the tiny forest has continued to bring the school community together. Students have made guides to explain their work and high school-aged students mentored younger students throughout the project. One student made a sculpture of hands spelling “LIFE” in American Sign Language, and another made a documentary offsite link about the tiny forest for her senior project. Above all, the tiny forest seems to be thriving. “I am also proud of the outcome: the Tiny Forest itself is healthy and looks like it will become a meaningful place on our campus,” said Walsh.