Was this silk dress worn by an early employee of the National Weather Service?

Mystery code in the pocket tells a story about early forecasting.

Mystery code in the pocket tells a story about early forecasting.

Sometimes a dress is just a dress. In this story, a dress becomes a kind of time travel portal, where we get to return very briefly to the Industrial Revolution and learn about the history of weather forecasting on the frontiers of North America in the 1800s.

Three views of the 1880s silk bustle dress in which crumpled bits of paper containing a code were found. The pocket where the code was found is located under the overskirt at the right hip. (Image credit: Sara Rivers Cofield)

The story starts in 2013 in an antique mall in Maine, where Sara Rivers Cofield sees a beautiful brown dress for sale. Rivers Cofield is an archeologist who also collects old dresses and handbags for fun. She loved this particular dress’s beautiful metal buttons and elaborate bustle.

Once she got the dress home she found a secret pocket hidden under that bustle, inside the seams of the skirt. Upon further inspection, she also found crumpled bits of paper inside the secret pocket.

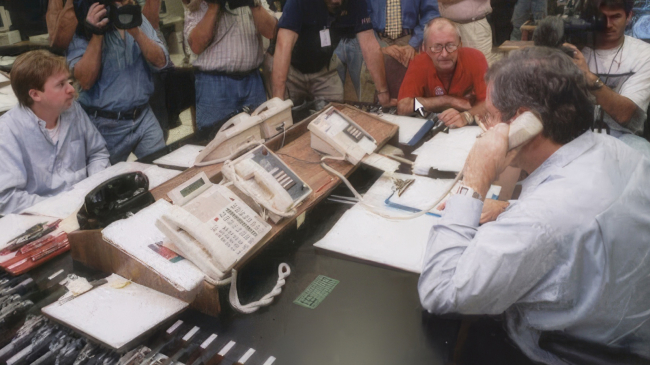

She recognized that both the dress and the paper were likely from the 1880s. What she couldn’t decipher was the meaning of messages written on the paper – lines of text, many beginning with a place name, followed by seemingly random verbs and nouns.

Bismark, omit, leafage, buck, bank

Calgary, Cuba, unguard, confute, duck, fagan

Spring, wilderness, lining, one, reading, novice.

“There are also numbers between the lines, each line is marked off with a different color, and there are weird time-like notes in the margin; 10pm, 1113PM, and 1124 P. I feel like those clues actually DO point to code of some kind,” Rivers Cofield wrote soon after on her blog about old costumes and dresses offsite link. “I'm putting it up here in case there's some decoding prodigy out there looking for a project.”

Soon after, her online plea went viral, as the sentences began intriguing people from all over the world. Subscribers to online forums like Reddit put forth theories:

Love notes?

Dress measurements and orders?

Illegal gambling?

War code? Maybe the woman who owned the dress was a spy!

Several theories were quickly dismissed by the more experienced antique dealers and code breakers – the messages couldn’t be from the American Civil War, for example, because the dress seemed to date from the 1880s, some twenty years after the conflict ended.

Many online comments argued that it was likely a type of telegraphic code, related to the new communications infrastructure that began crisscrossing the globe in the 1800s. This seemed much more likely.

The invention of the telegraph changed how news was shared in the mid 1800s. Suddenly, people were able to send messages from town to town quickly. In the United States, a series of long or short taps made by a person on one end of the wire were recorded by an operator on the other end as dots and dashes. This meant messages could be tapped into a machine in one town and heard and recorded in another town hundreds of miles away in just a matter of minutes.

To keep wired messaging via telegraph inexpensive, a sort of shorthand was developed.

“Since telegraph companies charged by the number of words in a telegram, codes to compress a message to reduce the number of words became popular,” wrote researcher Wayne Chan from the University of Manitoba, when explaining the topic in an academic paper published in August of 2022 offsite link.

For example, Chan notes, “A phrase such as “The crew are all drunk” may be substituted with a codeword such as “CRIMPING.”

It's not all that different from what people do with texts on their cell phones today, Chan explains.

Chan knew that telegraphic codes were also often created to ensure privacy, since telegrams passed through so many hands before and after being sent. Law enforcement agencies, for example, often used secret codes. But so did mining companies, grocers, seed companies, banks, railways and even movie makers in the early days of cinema. During the telegraph era, hundreds of codebooks were published. What bothered Chan – and many other code breakers across the internet – was that no one could figure out which particular codebook this series of words came from.

What did the messages mean?

Although ten years had passed since Rivers Cofield had first found the messages stuffed in the hidden pocket, no one had cracked it. The silk dress cryptogram, as it came to be known, was considered by expert and amateur cryptogram lovers the world over to be one of the top 50 unsolvable codes in the world.

Chan, who works as an analyst with the Centre for Earth Observation Science at the University of Manitoba offsite link but solves codes as a hobby, decided to dedicate himself to answering those questions once and for all.

After a fruitless search through approximately 170 telegraphic codebooks, he decided to learn more about the era of the telegraph. Chan came across an old book called “Telegraphic Tales and Telegraphic History” which contained a section about the weather code used by the U.S. Army Signal Corps. The examples in the book seemed to look similar to the codewords from the dress, leading him to believe that the code was related to weather.

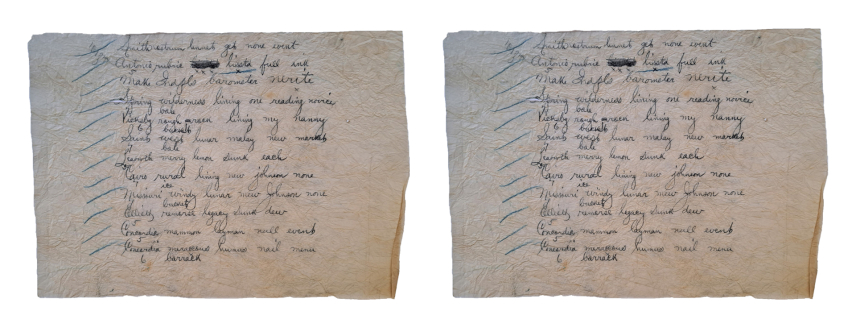

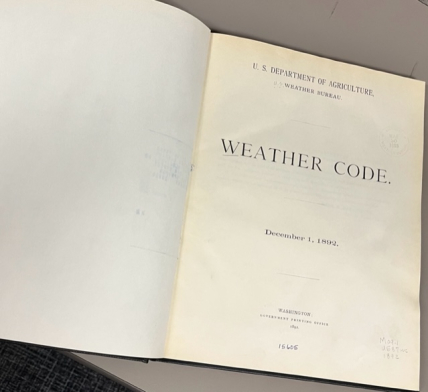

The invention of the telegraph had transformed many things, including weather forecasting. For the first time in history, news about the weather could travel faster than the weather itself, Chan explains. But weather observations, consisting of a number of meteorological variables, had to be condensed, just like other telegraph messages to save money. Code books were published for the weather observers to use. So it seemed likely that the book he would need to translate the code from that dress was one used by the Army Signal Service Division of Telegrams and Reports for the Benefit of Commerce in the 1870 to 1891 offsite link, a bureau that would eventually become NOAA’s National Weather Service.

There were some excerpts of such books online. But Chan knew he needed the entire book if he really wanted to decode all of the messages conclusively.

Many hours of dedicated sleuthing and academic research brought him to Katie Poser, the librarian at NOAA’s Central Library in Silver Spring, MD, who was able to provide a PDF copy of a weather telegraph code book, published in 1892. It wasn’t the exact book Chan needed, but it did help him realize he was on the right track.

Using the NOAA resource that Poser sent to him and some other resources, Chan deduced that the messages were from Signal Service weather stations in the U.S. and Canada.

Each line written on the papers indicated weather observations at a given location and time of day, which was telegraphed into a central Signal Service office in Washington, DC.

The format of weather messages at the time were as follows:

Each started with the station location, which was unencoded, followed by codewords for temperature/pressure, dew point, precipitation/wind direction, cloud observations, and wind velocity/sunset observations.

So for example,

Bismark, omit, leafage, buck, bank

Was code for:

BISMARK Station name: Bismarck, Dakota Territory (in present-day North Dakota)

OMIT Air temperature: 56 F Barometric pressure: 0.08 in Hg (Note that only the fractional part of the pressure value was telegraphed, unless the station was west of the 97th meridian or the pressure was below 29.4 in Hg or above 30.38 in Hg). In this case, the actual reading was 30.08 in Hg)

LEAFAGE Dew point: 32°F Observation time: 10:00 p.m.

BUCK State of weather: Clear Precipitation: None Wind direction: North

BANK Current wind velocity: 12 mph Sunset: Clear

Code cracked! Mystery solved!

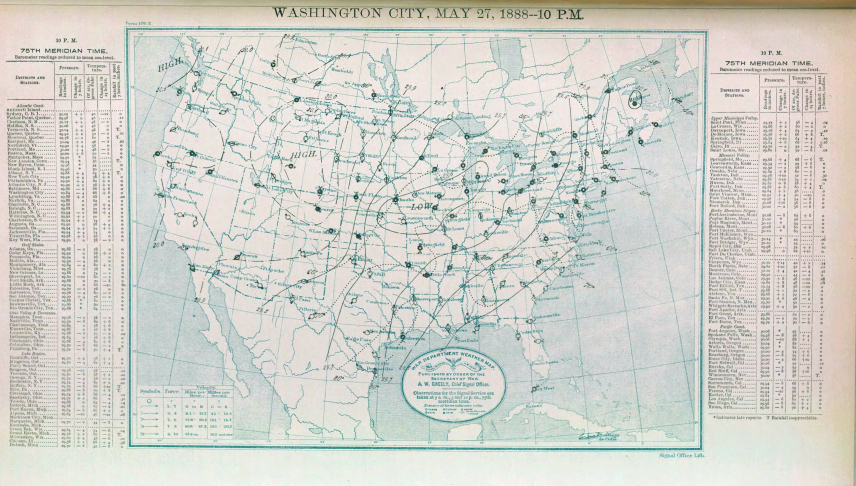

Further research using old daily Signal Service weather maps provided from the NOAA Central Library also allowed him to deduce that those observations were taken on May 27, 1888.

Poser notes that although this particular call had an unusual outcome, calls of this sort are not unusual for the NOAA Central Library, which is a public resource open to all citizens.

“It was interesting to see how far the impact of the Weather Service went,” Poser says, noting that she didn’t know about weather code books before the inquiry. She did know about NOAA’s relationship with the former Army Signal Service. “We were glad we could help. We don’t want to gatekeep any of this information. It should be accessible to anyone that wants or needs it.”

Not all of the questions about the dress have been answered. We may never know, for example, who owned the dress or why she had weather codes stuffed in a hard-to-access pocket near her petticoats one spring day. We know that hundreds of men and women were volunteer weather observers for the Smithsonian in the 1800s. But they mailed in their weather observations via the U.S. Postal Service, and would not have used telegraph codes.

Rivers Cofield also notes that the dress – although beautiful and fancy to our modern eyes – was not exactly what someone would wear to a ball. It was more like the ‘business casual’ of the day, and to her that does indicate it might have been worn to work.

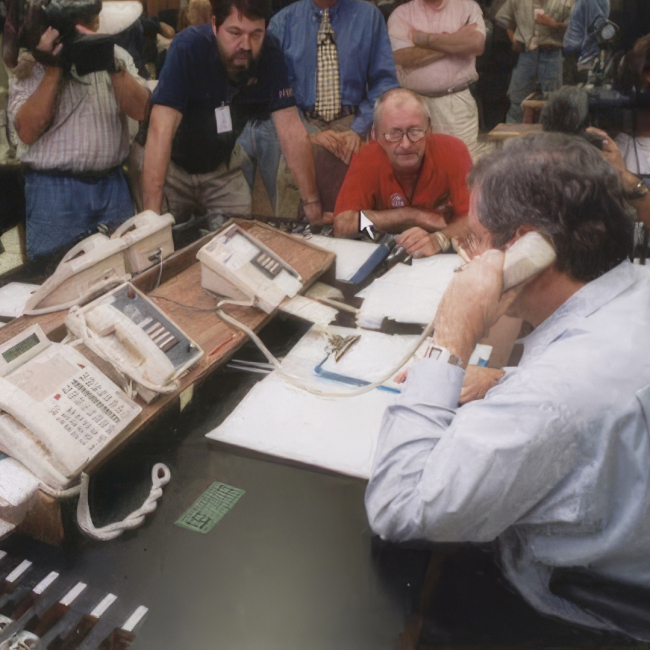

Chan has also documented that a number of women worked as clerical staff at the Washington, D.C. offices for the Army Signal Service in the 1880s.

A small label inside the dress has the word “Bennett” written on it. But Chan’s own attempts to conclusively connect any woman named Bennett with the staff of the D.C. Signal Service office proved futile. There was a man named Maitland Bennett working there as a clerk during this time period, and his wife might have been a possible candidate for owning the dress, but she was eight months pregnant when the weather observations were taken and unlikely to have been wearing the dress at the time. And, there’s no way to know when that label was attached to the dress or if it denoted ownership in the 1880s.

“Everybody loves a mystery,” Rivers Cofield says.

For now, Chan is pleased that his ability to crack the code provided a little bit of attention for a long forgotten part of history, calling it “a bygone time when the telegraph ushered in a new era for operational meteorology.”

For press inquiries, please email heritage.program@noaa.gov.