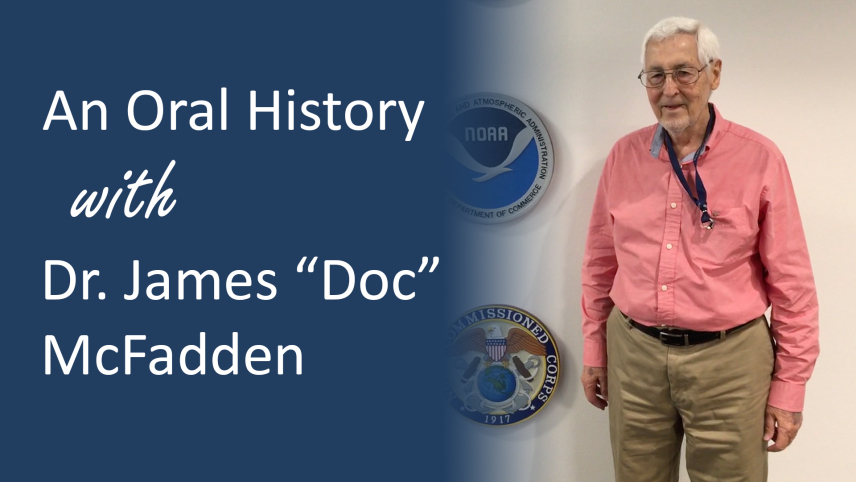

This oral history was conducted by Molly Graham in 2020 as a part of the NOAA 50th Anniversary Oral History Project.

Tenure at NOAA: 1965-2020 (Image credit: NOAA Heritage)

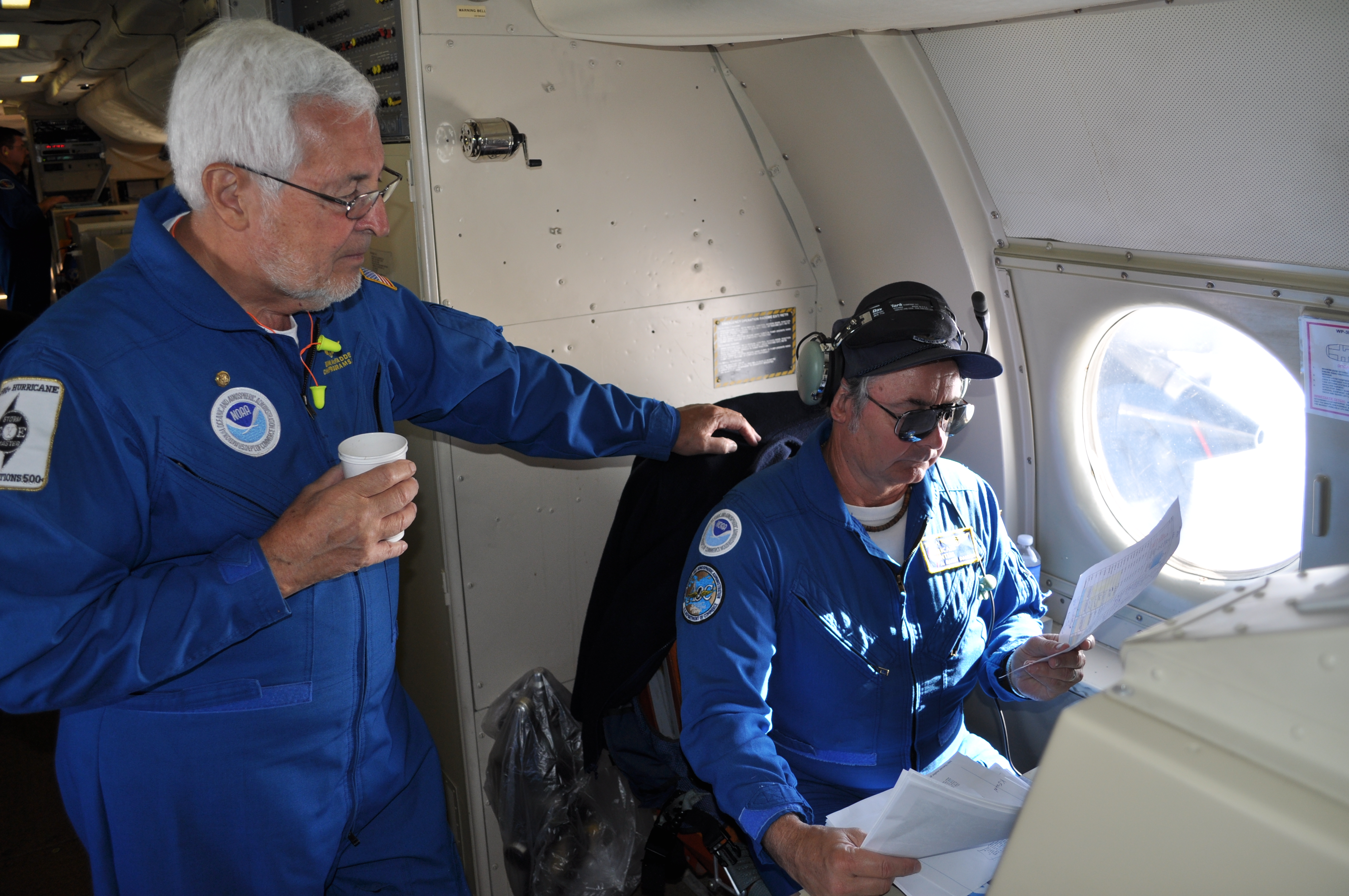

Dr. James “Doc” McFadden was a dedicated public servant who, over the course of his 57 year career, immeasurably influenced the evolution of airborne data collection at NOAA. Dr. McFadden most recently served as the NOAA Aircraft Operations Center Programs Chief, responsible for coordinating all research projects on NOAA’s aircraft, including our Gulfstream IV-SP and two Lockheed WP-3D Orion hurricane hunter aircraft.

Dr. McFadden played a key role in coordinating thousands of projects on more than two dozen aircraft of various types, makes, and models, including helicopters, seaplanes, fixed-wing light aircraft, heavy multi-engine propeller aircraft, and high-altitude jets.

In addition to his significant contributions to meteorology and the understanding of tropical cyclones, he holds the Guinness World Record for longest career as a hurricane hunter. Dr. McFadden flew his first mission to Hurricane Inez on October 6, 1966 and his final flight on September 22, 2019, at the age of 85, into Hurricane Jerry. He flew through more than 50 hurricanes on various aircraft during his career, passing through the eye a total of 590 times.

Dr. McFadden passed away on September 28, 2020. We salute him, his incredible career, and all his contributions to the NOAA family.

Hear a snippet of the interview recorded on Jan. 8, 2020 in Lakeland, Florida:

Listen to the full interview with James "Doc" McFadden.

Transcript:

On flying a hurricane hunter plane into Hurricane Hugo:

MG: I’ve seen some videos of the eyewall penetration, and that seems a little exciting.

JMF: Well, eyewall penetrations, that’s a different ballgame. Flying hurricanes, that’s a different ballgame. Flying hurricanes, flying tornadoes, which we do, they can get a little interesting. I’ve been in some good ones.

Certainly, Hugo comes to mind. I don’t know whether you heard about the Hugo incident. We were the first aircraft in Hugo, flying at fifteen hundred feet, the plane I was in. [...] The pilot finally says, “We’re going to make our penetration now, so take your seats.” We sat down, and I looked at the radar, and I said, “Oh my goodness.” I knew that we shouldn’t be penetrating this thing at fifteen-hundred feet. But we did, and we’re here to talk about it, but barely. It was supposedly a category two storm, and it was a category five.

We had a hundred and eighty-nine knots of wind in the eyewall, and we lost an engine in the middle of the eyewall. There was extreme turbulence. It was not a pretty sight. Got into the eye, and we were going down, not up. I think we ended up about seven hundred and fifty feet above the surface before they recovered. Then, once they recovered, they were able to climb in the eye and get up to a safer altitude, get out, and get back to Barbados. But it was one of my nine lives. I say I have nine lives; that was one of my nine lives.”

On never being afraid to fly into a hurricane:

JMF: Sure, guys get paid a paltry hazard duty fee for flying hurricanes, but the planes are certainly up to it, the crew is more than capable.

So I would never ever be afraid to get on an airplane into a hurricane. I just wouldn’t. A category five? Eh. Category fives often are not as rough as categories ones and twos that are rapidly intensifying. I guess you use an element of danger, but it’s not dangerous to the point where people are going to worry about not coming back from the next flight. Why is it important? Extremely important. It’s important to forecast. It’s important to improving the forecast. We’re research guys over here. We’re developing the tools to help the Weather Service improve, track an intensity forecast. We’ve developed the tail Doppler radar to a high standard now. It’s being used in real-time in the forecast models. The jet flies around the storm, drops the sondes, which are all assimilated into the models, which have proved to improve the track forecast. So we’re really providing data that helps to improve all the forecasts, which, in turn, provides the public with much better information. They used to say – maybe they still say, “It costs a million dollars a mile to prepare the coastline for a hurricane” – just preparation. If you can reduce that, by improving the track forecast, cut down your zone of warnings, you’ve saved a lot of money.

People want to know three things. They want to know when is it going to come, where is it going to go, and how strong is it going to be when it gets there. Well, when is it going to come? That’s a crapshoot. That’s climate. It’s going to come sometime, but we don’t know when. Where is it going to go? We got a pretty good handle on it now, where is it going to go? How strong is it going to be when it gets there? We’re improving that all the time. We got two P3s now. Next year, they’ll be both up and running. We had the wings replaced on both of them.

So we got two strong airplanes. We’ve got a lot of new instrumentation. We really are looking forward to the next season. I think it’s going to be gangbusters.