This oral history was conducted by Molly Graham in 2019 as a part of the NOAA 50th Anniversary Oral History Project.

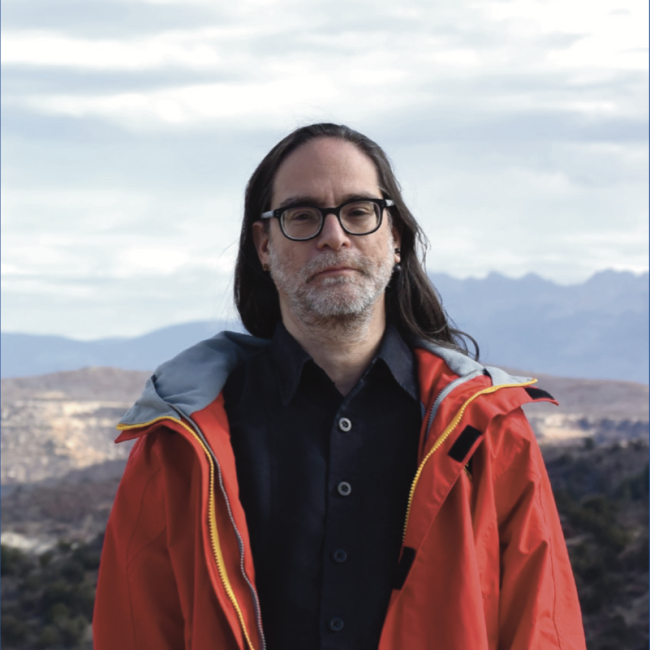

Tenure at NOAA: 1984-present (Image credit: NOAA Heritage)

Steven Wilson is the director of NOAA’s seafood commerce and certification program, which ensures seafood safety through inspections, training, and international partnerships. After growing up overseas in a military family, Wilson started his career in food inspection first as a lab technician for a packaged salad company and later as a poultry inspector for the USDA. His background in food science led him to NOAA in 1984 where he began inspecting seafood at a plant in Camp Hill, Pennsylvania.

Wilson is credited, among many other fascinating career experiences, with contributing to a more robust end-to-end system for inspecting food — standards that are now used worldwide. He was also in charge of NOAA’s response to testing and ensuring seafood safety in the aftermath of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

Hear a snippet of the interview recorded December 7, 2019:

Listen to the full interview with Steve Wilson.

Transcript:

On growing up in the Philippines on a military base:

MG: Tell me why being in the Philippines as a teenager was so great.

SW: Well, I had been involved in the Boy Scouts before that, very much involved. In the Philippines and in the military bases overseas, the Boy Scouts were king. The military wanted to do everything they could for the dependents. So Major General Manor – I’ll never forget his name – he was the commander of all of the 13th Air Force for the whole Pacific region. He was extreme in his support for the Boy Scouts. Our unit was sponsored not by a church like many other units, but by the jungle survival school, the people who taught the pilots what to do when they crash. So they would take us out. We had all sorts of equipment. We had buildings. Everything was set for us. Our troop grew to about a hundred and twenty boys – very large. On a monthly basis, we went somewhere – everywhere around the Philippines. Weekly, there was always something going on on the base. Once you hit Eagle Scout over there, at the time, if you wore your uniform, you were allowed to fly what the military calls “space available” without your sponsor, without my dad. So if we got our uniforms on, we could actually fly to Japan and spend a couple of days in Japan and then come back. We would do things like that. It was all the support of the Boy Scouts and everything else, and it was extreme, truly extreme.

MG: Were there a lot of other American families there?

SW: Yes. At the time, it was the largest military installation in the world. Sixty-six thousand people lived there – very big.

MG: That’s like a city.

SW: Big city. Then, a few years later, after I left, in 1981, Mount Pinatubo erupted, basically had to evacuate. We were trying to get out of that base anyway as the U.S, and it’s still there. I went back to visit about fifteen years ago, and a lot of the buildings that I remember were still there, some were gutted. They turned the high school into the University of the Philippines, and things like this, but essentially, it is not the same base it ever was. It started diminishing about two years after I got there.

MG: Because of the volcano?

SW: No, it was more along the lines that we didn’t necessarily need to be placed in different areas. The planes could fly longer faster. That was the staging area. When I was there the second time, that was the staging area for Vietnam. In fact, I was there in Vietnam – if you remember the headlines – you’re too young to remember. If you remember the headlines, when the POWs [prisoners of war] came back, one of the POWs came off the plane, said, “God bless America.” I was fifty feet away from him. We saw the first POWs coming back. They came in and talked to our school as part of their therapy. It was a very interesting time along those lines.

On improving seafood quality assurance:

MG: Your position changed again in 1996.

SW: Yes. My boss, at the time, wanted to have an internal affairs division. I said, “Well, can we call it quality assurance instead?” More improvement versus going after people. He said, “Sure.” So I became the chief quality officer at that point. That’s a misnomer that implies staff. I didn’t have anybody. It was just me. I worked hard for almost twenty years, trying to make sure that we had good procedures in place, that we did science-based information that the inspectors were using critical thinking, moving up. So a lot of was trying to improve the service. So that’s why I’m trying to say quality assurance versus: “You’re not doing your job. We’re going to fire you.” Some of that did happen, but it was a very rewarding time for anybody with a technical background.

MG: What do you mean?

SW: I had the opportunity to use not only the food science I learned and be able to talk to the scientists, but I also had the opportunity, through my association with the American Society for Quality and some of these other certifications to utilize good, quality management thinking towards – how do we address human behavior. We’re still doing this, but human behavior being: how do I make sure inspectors assess the same plant consistently? How do I make sure that I can review a report and know they did or didn’t do their job, things like that to make it easier for everybody concerned to do a good, sound level of performance. Some of it’s easy – let’s get a checklist so that we know they’re at least covering these. Some of it’s not so easy. When you’re reading a report – did they spit back the same information they’ve always spit back? How do I know they actually did it? There’s different ways of doing that. So we instituted internal audits, and I became basically the manager of what goes into the inspection manual and how it’s written, including, what do we actually put in there. You can overdo that. You can write down everything to the point where people don’t think. It was a very good time, and I would get an opportunity to see the operations of the field and get out there and really enjoy it.

MG: It’s interesting that you were doing such advanced and technical work without having finished your college degree yet.

SW: Yes. They would tell me that quite often – “Well, Steve doesn’t have a degree. He’s doing good.” “Thanks.” Yes, I didn’t have to finish the degree. I just said, “I’m going back. I want to finish this. I really do. Then, I got the bug. So I finished that, and then went and got my master’s right away. A master’s in business administration. The reason I did that is because this unit operates like a business. We set a fee. We’re trying to figure out the budgets. Did we cover our costs, etcetera? So I really wanted to understand business operations better. That was actually a very smart decision. I’ve even recommended when I leave – “You find businesspeople who help manage this.” The technical side of food inspection is actually easier to find than anything else. It’s managing this from a government agency’s perspective, but like a business that makes all the difference in the world. So I think we’ve been very successful because of that. I actually tried to get a Ph.D., worked on it for ten years, but family, working full-time, everything else – I just couldn’t get it done. At the time, I hadn’t been into this leadership position. I was still the chief quality officer. Then I became what they called the assistant for quality and technology. I was the science-based side. I said, “Well, a Ph.D. could help.” Well, Ph.D.s honestly, are for research, and I’m not in research anymore. I said, “Okay, moving on.” I might get more master’s or master certificates, but the Ph.D. was a desire, not a requirement.