Hi everyone, my name is Nicole, and I’m a 2022 Hollings scholar. This summer, I interned at the Kachemak Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve (KBNERR) in Homer, Alaska. I worked as a part of the Harmful Species Program, with my mentor Jasmine Maurer, the lead of the program. My project specifically focused on how we can make crab traps more effective for marine invasive species, such as the European green crab (Carcinus maenus).

Kim Schuster (left), a harmful species biologist at Kachemak Bay NERR, holding a hard-wire shrimp trap, and 2022 Hollings scholar Nicole Reynolds (right) holding a modified fukui trap in one hand, and five other fukui’s in another hand. (Image credit: Jasmine Maurer)

Project background

As European green crabs aren’t documented in most of Alaska yet, we’re working on early detection monitoring, which KBNERR has been doing since 2006. Last summer, European green crabs were spotted on Annette Island, which is located in Southeast Alaska. This new detection is sending out alarms and is inspiring advancements in trap efficacy. Some traps we use for invasive species monitoring are very bulky and heavy, which make them difficult to deploy for early detection and rapid response to European green crab. Since Alaska is so large, it can be difficult to get to certain trapping locations (we might need to use a boat or float plane!) so we need lightweight, efficient traps for our trapping events. To make a more lightweight and less bulky option compared to what is often used, I modified a standard crab trap, the fukui trap, and attached weights to make the entrance opening wider.

Example of a day trapping crabs

The time we leave is very dependent on the tide, as we need to set the crab traps at the lowest tide so they are in the water for as long as possible. Kachemak Bay has some of the largest tide swings in the world (up to 25 feet in a day!), so we have to be careful with timing. Depending on the site we’re trapping at, we’ll either take our research boat or just drive and walk down the beach.

Here’s what a day of crab trapping might look like for our site across the bay, Jakolof!

7:00 a.m.

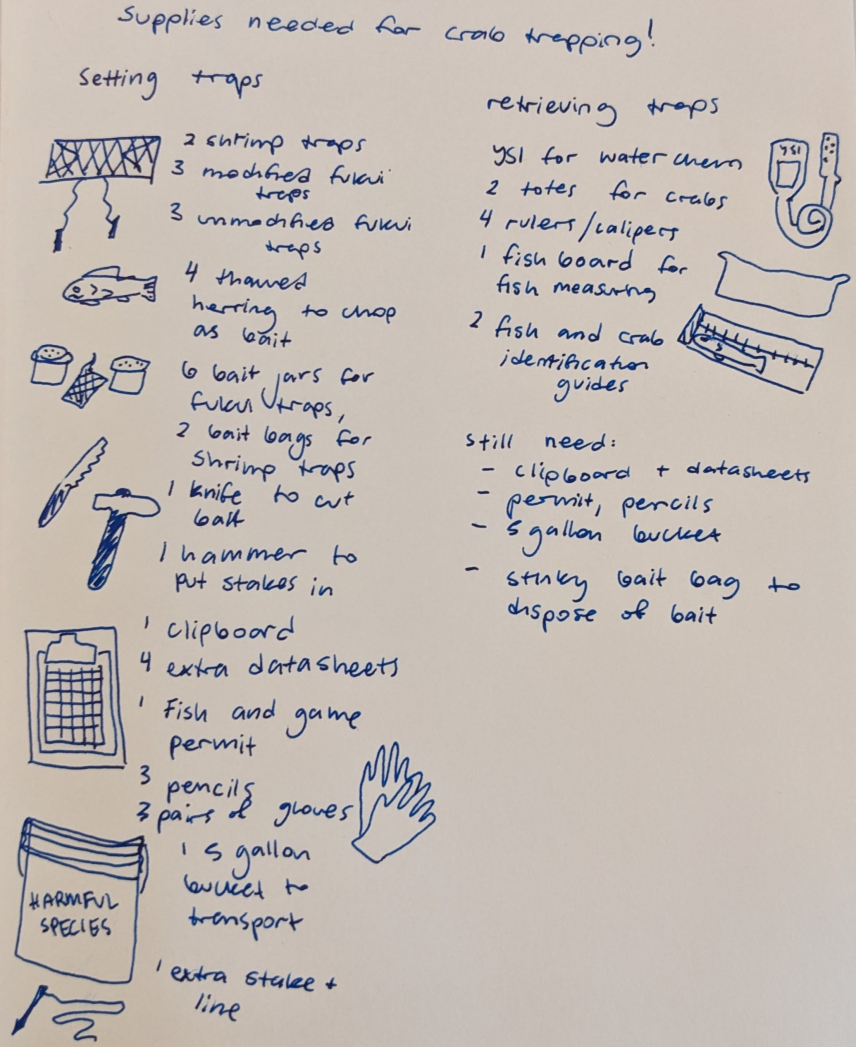

Wake up, make breakfast, pack lunch and prepare supplies to bring to the boat. Depending on if we are setting the traps or retrieving them, we have different lists of things we need to bring.

7:45 a.m.

Leave the office/bunkhouse and bring trapping supplies to the Homer Harbor and load them onto our research boat, the Whaler. Then, we ride 45 minutes across the bay to our site, Jakolof Bay.

9:00 a.m.

Load trapping supplies off the boat at the Kasitsna Bay Labs and onto a truck. Here, we drive them to Jakolof through back roads. There are no roads that connect from Homer to the other side of the bay, so anything on the other side needs to be boated over!

9:45 a.m.

Arrive at the study site. If we’re setting the traps, we’ll pick a sampling area and set up traps in 30-foot intervals apart. We open the traps, cut up bait, and put them in jars, then close everything up and hammer stakes into the ground.

If we’re retrieving the traps, we’ll start at the first trap we set and pull it out of the water. We’ll open it up, pick up all species within the trap and identify, measure, and sex them (if possible). Any non-invasive species are released. This season, we didn’t find any invasive European green crab!

11:00 a.m.

Pack up everything and load the boat back up. Once we ride back, we head over to the lab and clean up all the gear. Depending on the day, we might go back to the office and enter the data into the database, work on graphs and data management in R, or do more field work!

Another type of invasive species monitoring we do in affiliation with the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center offsite link is focused on invasive tunicates. The invasive tunicates are a type of marine invertebrate that builds up on surfaces and can destroy fishing or mariculture equipment and smother native species. We have PVC plates in harbors across the bay and every quarter we swap the plates and collect the “biological fouling” that collected on the plates. Biological fouling refers to all of the marine plants, animals, microbes, and more that have grown on the plate. It’s very fun to learn about what kinds of invertebrates grow on the plates (bryozoans, sponges, and tunicates galore!), and can get very messy too!

4 p.m.

Our workday ends a little early since we started early to follow the tides. Alaska has so many things to offer – our intern cohort goes and explores Homer often! We get to check out the

farmers market, go thrifting, go on backcountry hikes, and see wildlife like moose, eagles, and bears!

The NOAA Hollings scholarship is such a fantastic opportunity to learn more about a career in science, network with amazing people, make new friends, and explore new places. It has already taught me so much about myself and what I want to do with my future. If you’re an interested student, definitely apply!

If you are interested in the Hollings Scholarship Program, apply by January 31, 2024. For other NOAA student opportunities, visit our NOAA Student Opportunities Database.

Nicole Reynolds is a 2022 Hollings scholar and marine biology and oceanography double-major at the University of Washington Seattle.