Rip currents are powerful, channeled currents of water flowing away from shore. They typically extend from the shoreline, through the surf zone, and past the line of breaking waves. Rip currents can occur at any beach with breaking waves, including the Great Lakes.

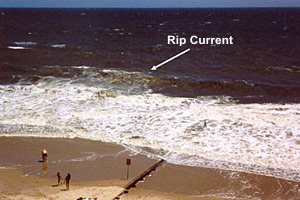

Rip currents most commonly form at low spots or breaks in sandbars and near structures such as groins, jetties, and piers. Rip currents can be very narrow or be hundreds of yards wide. The seaward pull of rip currents also varies: sometimes the rip current ends just beyond the line of breaking waves, but other times, rip currents continue to push hundreds of yards offshore.

Rip currents form as incoming waves (#1 above) push water toward the shoreline (#2 above), which creates an imbalance of water piling up in the surf zone. To stay in balance, the water seeks the path of least resistance back through the surf, which is typically a break in the sandbar (#3 above). This is where the rip current is the strongest. Once the flowing water passes through the narrow gap, it begins to spread out (#4), considerably weakening the velocity and strength of the rip current circulation.

Rip currents are often referred to as drowning machines by lifeguards and are the leading cause of rescues for people in the surf. They are particularly dangerous for weak or non-swimmers, but a strong rip current is a hazard for even experienced swimmers. Rip current speeds are typically 1-2 feet per second, but speeds as high as 8 feet per second have been measured. That is faster than an Olympic swimmer! Drowning deaths occur when people, pulled away from the shoreline, are unable to keep themselves afloat and swim to shore. This may be due to any combination of fear, panic, exhaustion, or lack of swimming skills. Once people become tired, they can easily go under without flotation to hold onto.

The United States Lifesaving Association estimates that the annual number of deaths due to rip currents on our nation's beaches exceeds 100. Rip currents account for over 80% of rescues performed by surf beach lifeguards.

Make sure you stay aware of the dangers of rip currents and learn how to protect yourself.

Dispelling the Myth of the Rip

Rip currents are sometimes incorrectly called an “undertow”. However, a rip current is a horizontal motion, like a treadmill that carries people away from the shoreline. It is not something that pulls you under.

Another incorrect term used is "rip tide". While rip current strength can be affected by the tide (intensity is enhanced during the hours around low tide), rip currents are not tides and can exist during any part of the tidal cycle.

Rip Currents: Where's the Rip?

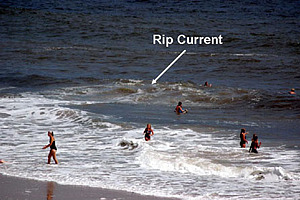

Signs that a rip current is present can be very subtle and difficult to identify, especially when the ocean is very rough. However, at times they can be spotted, especially from higher vantage points than the water's edge. Some clues include:

- A narrow gap of darker, seemingly calmer water flanked by areas of breaking waves and whitewater.

- A channel of churning/choppy water that is distinct from surrounding water

- A difference in water color, such as an area of muddy-appearing water (which occurs from sediment and sand being carried away from the beach).

- A consistent area of foam or seaweed being carried through the surf.

You may be able to observe the water flowing away from the beach with the stronger rip currents. If you are ever in doubt, ask a lifeguard at a guarded beach and they will let you know if they have observed any rip currents.