Ordinary Cell

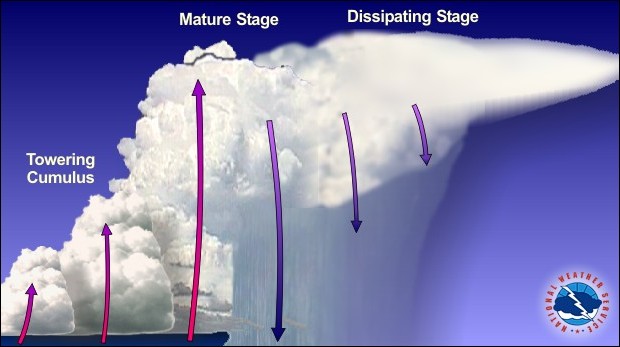

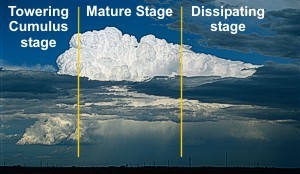

Also called a "pulse" thunderstorm, the ordinary cell consists of a one-time updraft and one-time downdraft. In the towering cumulus stage, the rising updraft will suspend growing raindrops until the point where the weight of the water is greater than what can be supported.

At this point, drag between the air and the falling drops begins to diminish the updraft, which allows more raindrops to fall. In effect, the falling rain turns the updraft into a downdraft. With rain falling back into the updraft, the supply of rising moist air is cut-off, and the life of the single cell thunderstorm is short.

While hail and gusty wind can develop, these occurrences are typically not severe. However, if atmospheric conditions are right and the ordinary cell is strong enough, more than one cell can potentially form and can include microburst winds (usually less than 70 mph/112 km/h) and weak tornadoes.

Multi-cell Cluster

A thunderstorm may consist of just one ordinary cell that transitions through its life cycle and dissipates without additional new cell formation, but they often form in clusters, with numerous cells in various stages of development merging together.

While each individual thunderstorm cell in a multi-cell cluster behaves as a single cell, the prevailing atmospheric conditions are such that as the first cell matures, it is carried downstream by the upper level winds, with a new cell forming upwind of the previous cell to take its place.

The speed at which the entire cluster of thunderstorms move downstream can make a huge difference in the amount of rain any one place receives. Frequently, as an individual cell moves downstream, additional cells form on the upwind side of the cluster and move directly over the path of the previous cell.

The term for this type of pattern when viewed by radar is "training echoes". These training thunderstorms produce tremendous rainfall over relatively small areas, leading to flash flooding.

Sometimes the atmospheric conditions encourage vigorous new cell growth – they form so fast that each new cell develops further and further upstream, appearing as though the thunderstorm cluster is stationary or moving backwards against the upper level wind.

Tremendous rainfall amounts can be produced over very small areas by back-building thunderstorms. In 1972, 15" (380 mm) fell in six hours over parts of Rapid City, SD, due to back-building storms.

Multi-cell Line (Squall Line)

Sometimes thunderstorms will form in a line that can extend laterally for hundreds of miles. These "squall lines" can persist for many hours and produce damaging winds and hail.

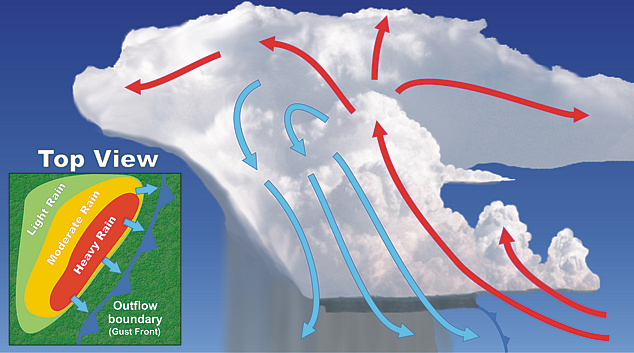

Updrafts, and therefore new cells, continually re-form at the leading edge of the system, with rain and hail following behind. Individual thunderstorm updrafts and downdrafts along the line can become quite strong, resulting in episodes of large hail and strong outflow winds that move rapidly ahead of the system.

While the leading edge of squall lines occasionally form tornadoes, they primarily produce "straight-line" wind damage, a result of the force of the downdraft spreading horizontally as it reaches the Earth's surface.

Long-lived, strong squall lines are called "derechos" (Spanish for “straight”). Derechos can travel many hundreds of miles and can produce considerable widespread damage from wind and hail. Learn more about derechos.

Often along the leading edge of the squall line is a low hanging arc of cloudiness called the shelf cloud. This results from rain-cooled air spreading out from underneath the squall line like a mini cold front. The cooler, dense air forces the warmer, less dense air up. The rapidly rising air cools and condenses, creating the shelf cloud.

Supercell Thunderstorms

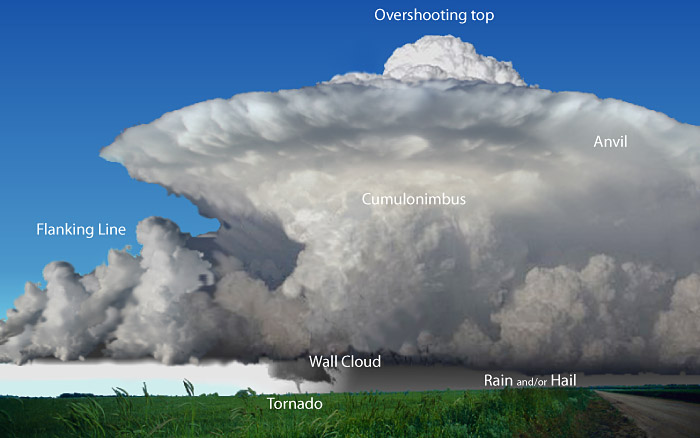

Supercell thunderstorms are a special kind of single cell thunderstorm that can persist for many hours. They are responsible for nearly all of the significant tornadoes produced in the U.S. and for most of the hailstones larger than golf ball size. Supercells are also known to produce extreme winds and flash flooding.

Supercells are highly organized storms characterized by updrafts that can attain speeds of over 100 mph (160 km/h) and are able to produce giant hail with strong or even violent tornadoes. Downdrafts produced by these storms can produce downbursts/outflow winds in excess of 100 mph (160 km/h), posing a high threat to life and property.

The most ideal conditions for supercells to occur are when the winds are veering, or turning clockwise, with height. For example, in a veering wind situation, the winds may be from the south at the surface and from the west at 15,000 feet (4,500 meters). This change in wind speed and direction produces storm-scale rotation, meaning the entire cloud rotates, which may give a striated or corkscrew appearance to the storm's updraft.

Dynamically, all supercells are fundamentally similar. However, they often appear quite visually different from each other, depending on the amount of precipitation accompanying the storm and whether precipitation falls adjacent to, or is removed from, the storm's updraft.

Based on their visual appearance, supercells are often divided into three groups:

- Rear Flank Supercell - Low precipitation (LP)

- Classic (CL)

- Front Flank Supercell - High precipitation (HP)

In low precipitation supercells, the updraft is on the rear flank of the storm, creating a barber pole or corkscrew appearance to the cloud. Precipitation is sparse or well removed from the updraft and/or is often transparent.

Large hail is often difficult to discern visually. With the lack of precipitation, no "hook" is seen on Doppler radar.

The majority of supercells fall in the "classic" category. The classic supercell will have a large, flat updraft base with striations or banding seen around the periphery of the updraft. Heavy precipitation falls adjacent to the updraft with large hail likely. These have the potential for strong, long-lived tornadoes.

High precipitation supercells will have...

- the updraft on the front flank of the storm;

- precipitation that almost surrounds updraft at times;

- the likelihood of a wall cloud (but it may be obscured by the heavy precipitation),

- tornadoes that are potentially wrapped by rain (and therefore difficult to see); and

- extremely heavy precipitation with flash flooding.

Beneath the supercell, the rotation of the storm is often visible as well, appearing as a lowered, rotating cloud, called a Wall Cloud, formed below the rain-free base and/or below the main storm tower updraft. Wall clouds are often located on the trailing flank of the precipitation.

The wall cloud is sometimes a precursor to a tornado, which would usually form within the wall cloud.

With some storms, such as high precipitation supercells, the wall cloud area may be obscured by precipitation or located on the leading flank of the storm.

Wall clouds associated with potentially severe storms can:

- Be a persistent feature that lasts for 10 minutes or more

- Have visible rotation

- Appear with lots of rising or sinking motion within and around the wall cloud